World-Building

A Review of Future/Present: Arts in A Changing America

Eddie Torres, Grantmakers in the Arts

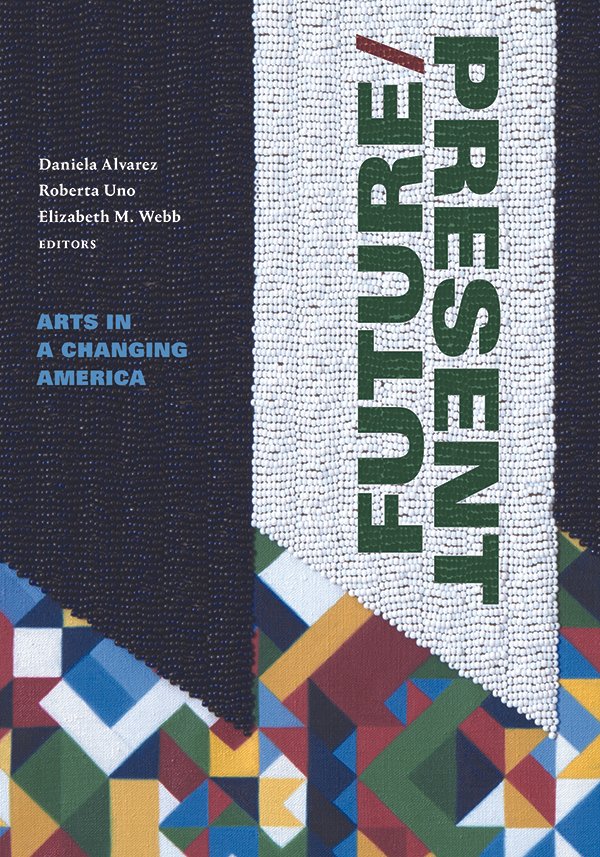

Editor(s): Daniela Alvarez, Roberta Uno, Elizabeth M. Webb

Duke University Press (Durham & London, February 2024) 568 pages

Cover art: Dyani White Hawk, Stealing Horses Back, 2016. Oil, vintage glass beads, thread on linen, 18×48 in.

Photograph by Rik Sferra. Courtesy of the artist.

Future/Present: Arts in A Changing America, edited by Daniela Alvarez, Roberta Uno, Elizabeth M. Webb, is a collection of essays reflecting on the cultural work toward racial justice in the U.S. today. An important effort that catalogues the why and how of contemporary cultural practice.

More importantly, Future/Present is an act of world-building. Future/Present presents the future of the world as we want it: A future rooted in the practices of our ancestors; A future that embraces the global majority and their cultural voices; A future that embraces intersectionality, – including racialized people, female-identifying people, gender-nonconforming people, and people with disabilities – as aesthetic forces that can work to replace racial capitalism with mutuality.

The work is a collection of over 100 essays by even more authors. No one review could possibly do it justice. But I will reflect on a few passages to illustrate this world-building.

Jeff Chang’s piece, “The Call,” which serves as the opening essay, contextualizes this moment in history. Chang articulates cultural justice as the healing of the erasure, suppression, and marginalization of people’s artistic and cultural practice. Further, he explains how Roberta Uno’s Ford Foundation grant program, Future Aesthetics, and subsequent Arts in a Changing America project have been fueled by the values of cultural justice. Chang calls out the lie that focusing support on predominantly White institutions (PWI) benefits all. Chang points out the racialized impact of the layoffs that resulted from the 2020 pandemic. “They have a big endowment. They’ll be fine,” we tend to say about institutions. But when layoffs occur, we must ask who will be fine? The building? The collection? The programs? Because it’s not the people. The Call is one to foreground racialized and other oppressed peoples in our cultural investments and places this call in a historical context that includes the present.

“We Are Part of This Land” is Carlton Turner’s piece on land and food reclamation by Black communities in the South. This is a hugely important piece that situates our nation’s construction through theft of land, of labor, and of culture – including cuisine – and how Black people in the South are taking them back. Turner points out the direct correlation between the states that mastered human trafficking pre-Civil War and those that have the highest incarceration rates today. He places this legacy in the relationship between land, food, and liberation.

Speaking on his own community, Turner explains that Utica, Mississippi is not a food desert. What Turner, and so many other communities, are experiencing is instead food apartheid, where some communities have it and others don’t, mostly based on race and class. Turner’s Mississippi Center for Cultural Production (Sipp Culture) is taking an intergenerational approach to community cultural and economic development through the lens of cultural and agricultural production – shifting the community’s dominant identity from consumers to producers.

As Turner explains, Black people psychologically connect land labor to sharecropping and enslavement. Sipp Culture is working to shift that ideology to one of empowerment and liberation. As he says, the Black community will thrive once the land is liberated and bears fruit.

“Huliau,” by Vicky Holt Takamine, traces the history of Hawai’i including the imposition of Christianity on Native Hawaiians, including the banning of their cultural forms such as hula. Women in the Hawaiian kingdom enjoyed the right to vote – a right they lost when Hawai’i became a US territory. As recently as 1997, the Hawaiian State Legislature introduced legislation that would restrict Native Hawaiian gathering rights. Takamine parallels her embrace of her cultural forms with the Hawaiian people’s organizing. As Takamine explains, “I see hula as resistance. I see hula as a tool for organizing community around issues that are facing Native Hawaiians. We have been able to reclaim our cultural practices through the hula. We have been able to regain our language through the hula. All the songs and dances, the chants, are in the Hawaiian language, and you have to study the language in order to be able to perform the hula, to understand the hula. Hula was my entrée into Hawaiian language, into Hawaiian culture.” The Native Hawaiian people have used their cultural forms as protest, affirmation, and self-determination for as long as colonization and beyond.

“Feminist Coalition and Queer Movements across Time: A Conversation between ALOK Vaid-Menon and Urvishi Vaid” is a moving intergenerational discussion of the interactions between art and activism. As Vaid says to ALOK: “It’s funny because you’re an artist with a political imagination, and I’m a political activist with an artist’s imagination.” ALOK reflects upon how transphobia is actually rooted in femme phobia, which is rooted in unacknowledged patriarchy that genders femininity, rather than critiquing the gendered system. ALOK identifies the search for legitimacy through single-issue advocacy, like gay marriage, as unprocessed trauma in the place of engagement with the deep existential pain of being different. ALOK reflects upon their performances as being about the intersection between race and transphobia but also about loneliness, which is universal.

“There is No Abolition or Liberation Without Disability Justice,” by Lydia X. Z. Brown, does a brilliant job of laying out how systems that have racialized and ableist outcomes interact and form social structures with racialized and ableist outcomes (i.e., outcomes that benefit the corporate class and are supported by the state). Brown tells the story of one punitive “treatment” institution for people with disabilities whose population is 90% people of color (85% Black and Latine). This institution receives referrals from adult developmental disabilities services systems, local education agencies, and the juvenile criminal legal system. Brown uses this story as one of many to elucidate how punitive all our nation’s social support systems are – so much so that losing a job inherently imperils our access to health care, housing, and not just livelihoods but lives. Brown courageously envisions a system of justice that is not centered on punishment but instead on restoration – for racialized and disabled people and us all.

In “We Begin By Listening,” Jeanette Lee shares how Allied Media Project collaborated on a citywide funder organizing initiative to shift the power dynamics between philanthropy and community organizations. The effort developed from a project called 12 Recommendations for Detroit Funders, shortly after the Ford Foundation committed to increasing their spending in Detroit following the city’s bankruptcy. The initiative calls for a deep participatory relationship between funders and community members that includes funders listening to community concerns and interrogating their own funding practices, those practices’ consequences – intended or not – and engaging in long-term structural investment in the community’s capacity for self-determination. These proposals reconsider the long-standing dynamic between funders and community members – relationship-building for world-building.

And, lastly in this reflection, is Eleanor Savage’s “A Call to Action” which is exactly that – a no-holds bar petition to her fellow White people to abandon resistance and fear and replace them with relationships built on humility and mutuality. GIA joins Savage as she calls upon our fellow actors in the cultural grantmaking ecosystem in a similar spirit; the work of world-building requires humility and mutuality.

This is a hugely important text - one from which you can gain sustenance for years. This book will sit alongside such classics as Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds by adrienne maree brown, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi, Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century by alice wong and On Intersectionality: Essential Writings by Kimberlé W. Crenshaw.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Eddie Torres is the president & CEO of Grantmakers in the Arts. They are a social change leader in the nonprofit, philanthropic and public sectors - currently serving as president and CEO of Grantmakers in the Arts. Torres served as deputy commissioner of cultural affairs for New York City, where they played a leadership role in the development of the city’s long-term sustainability plan, the city's first cultural plan and a study of and efforts to support the diversity of the city’s cultural organizations. Prior, Torres was a program officer with The Rockefeller Foundation, where they supported arts and culture, employment access, and resilience. Torres has also served at The Ford Foundation and the Bronx Council on the Arts, among other roles. Torres serves on the board of directors of United Philanthropy Forum, as well as serving on its Public Policy Committee. Torres holds a Master of Arts in Art History from Hunter College and a Master of Science in Management from The New School.