Relationship of Data and Funder Practice

Supporting Individual Artists with an Equity Lens

GIA Support for Individual Artists Committee

Why Do We Need Another Survey?

Grantmakers in the Arts (GIA) members have been working to promote and improve funding for individual artists for over 20 years. Early on in the life of GIA, members have continued to center the importance of providing support for individual artists. With this in mind, the GIA team and engaged members formed the Support for Individual Artists (SFIA) Committee, and it has been one of the most active groups of funders within GIA ever since. Over the years, the SFIA Committee has been an incubator for such projects as a scan of scholarly research on artist support, a panel review toolkit, a visual timeline outlining the history of artist support funding, the planning of the individual artist preconference sessions at the annual conference, and the development of a national taxonomy for reporting data, which was the starting point for this project.

In 2014, GIA released the A Proposed National Standard Taxonomy for Reporting Data on Support for Individual Artists. The project was launched in response to the significant gap in reliable and comprehensive benchmark data available on support that goes directly to individual artists. A preliminary scan revealed that while there is some data being accumulated by different organizations, it is incomplete, not comprehensive, and not tracked in a consistent manner by those institutions. So, in response, the Taxonomy of artist support was developed to serve as a national standard for collecting, comparing, and analyzing data on support programs for individual artists.

The primary goal of the Taxonomy was to establish benchmark data nationally on financial support provided to individual artists from public, private, and nonprofit grantmakers. A secondary goal of this project was to examine the potential for developing or modifying existing taxonomies and grant coding systems among organizations tracking this data to allow for consistent and parallel exchange of their data. This work was undertaken by the team of Alan Brown and John Carnwath from WolfBrown, and Claudia Bach from AdvisArts Consulting, working with GIA staff. There was a broad range of response from funders about their level of engagement with the idea of research on their work. Similarly, the results of the taxonomy survey showed a diversity of ways that funders value data and information and how they are able to imagine using data and analysis to further their work. After GIA underwent a period of leadership transition in 2017, the new GIA team and former co-chairs of the SIFA Committee, Tony Grant, Sustainable Arts Foundation, and Ruby Lopez Harper, Americans for the Arts, expressed a desire to revisit the taxonomy with fresh perspective.

Survey Objectives

In 2018 the SFIA Committee was in the midst of planning its programming for the year, and they turned to the Taxonomy as a guide for information on the state of the field. They quickly realized that the questions asked did not provide the information they were looking for so this sparked a new conversation on data: who is collecting data; what is being collected; and is this collection of data being done equitably. So, the Committee decided to take a survey that would ultimately address the question, “How can we further explore the nature of data and its relationship to purpose, assumptions, collection, harvesting, analyses, application, intention vs impact, planning, and equity?”

Methodology

The Committee transformed this survey idea into a research project and began by creating and administering an internal survey to Committee members in order to understand the nature and purpose of current data collection practices. The survey was then revised based on feedback and developed into a more suitable GIA member-field survey to reveal who is collecting data, how grantmakers are using data, where the data is coming from, and how it can be instrumentalized to create gateways toward equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Data Collected

The beta version of the survey was first sent to 20 GIA Support for Individual Artist Committee members, and 16 of the 20 members responded. An updated and abridged version of the survey was then deployed to 327 individual GIA member organizations, and 77 responses were received. The majority of respondents (62%) identified as local, state, or regional arts councils, with 10% from Family Foundations, and 13% Other (mostly nonprofits). The remaining 15% of respondents came from Intermediary, Independent Foundation, Public Charity, Private Operating Foundation, Charitable Trust, Donor Advised Fund, Community Foundation, and Corporate Foundation. Ninety percent of the respondents provide funding support to individual artists.

The 17-question survey consisted of qualitative and quantitative prompts. Qualitative data was captured through narrative responses and participant comments. Quantitative data was collected via category ranking metrics, coupled with a tally of frequently used general terms within narrative responses.

Visit Appendix A for the complete survey with responses.

Key Findings

The primary vehicles for collecting data are through online grant applications, reports, and surveys (89–90%). Forty-five percent of the respondents collect data through commissioned research, and 62% host focus groups.

Nearly all funders collect data from grant applicants (96%) and recipients (89%), while only 36% solicit information from non-applicants. The type of data varies, though a majority collect: artistic discipline (87%), race (70%), ethnicity (63%), gender (61%), disability status (52%), age (52%), and geographic information (52%). Other processes and initiatives that require data collection include: DEI initiatives, field surveys, strategic planning, and the post-application process.

Quick Takeaways

The most frequently collected data type is artistic discipline, yet the categorization of discipline and practices varies widely among funders. Some sort discipline by a handful of core categories (e.g. visual, performing, literary, media, traditional/folk) whereas others use sub-disciplines, genres, and other types.

More than 70% of funders use individual artist data to measure and evaluate progress towards goals, including geographic reach, DEI goals, program goals, and the impact of their funding programs.

While many funders use data to evaluate impact and measure progress towards program and equity goals, fewer use it to impact decisions in the grantmaking process. (44% report “yes” and 32% report “sometimes.”) Some funders who do not use data to impact decision-making say they do use it to inform program design and process.

More than half of funders (51%) believe the intention behind collecting data “sometimes” matches the impact. Open-ended responses include:

“We could do a better job here.”

“We are not necessarily collecting enough nor using it in the most impactful way.”

“We still collect more data than we meaningfully use.”

“We have collected the data for a long time and use a small subset.”

When asked with whom data is shared, most only shared data with staff (94%) and board (77%), with 20% reporting that data is shared with applicants. For the most part, data that is made available to the public through transparency policies or self-reporting do so in aggregate without linking personally identifiable information.

Overall, the survey responses suggest a need for further training of program staff, who are mainly responsible for evaluating and interpreting data (95%). There is expressed interest for learning more about best practices around data collection and evaluation, data security and how to make data actionable in pursuit of racial equity.

In response to these articulated inquiries, the following report contextualizes the survey findings within a framework that offers recommendations, resources, and case studies on best practices for collecting, analyzing, and securing data. Our analysis foregrounds future inquiries on equitable data collection in arts funding.

Best Practices for Collecting Data

Clarify and be able to express the reasons why demographic data is important to your organization.

It is key to establish at the board and leadership level an organizational commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion to ground the practice of collecting demographic data.

Staff needs to have a clear understanding of how data brings value to the work of the organization and how it connects to the values of your organization. Make sure that everyone is informed and put into writing why it’s important. It will take time to surface and discuss internal issues and concerns about how data brings value to your organization and how it connects to your organization’s values. For example, a value statement might be: “We are committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and we view data as an essential tool to practice this commitment.”

Develop systems for managing the data, especially taking into consideration data security. Do you have secure database software? Or access to a secure online database system?

Discuss and determine what data you will collect, and with whom it will be shared? Are you collecting data about your programs, staff, board, vendors, artists. If you are interested in asking grantee partners to share demographic data, ask yourself if you are you collecting and sharing your own data? It’s tough to ask others to do something that you are not doing. Consider building your organization’s commitment to sharing its own demographic data, explore how best to do it, and start there first.

Be transparent about why you are collecting data and how it will be used.

People want to know how and why you are collecting their data. So, tell them!

Allow people to “opt-in” or “opt-out” of data collection or to write-in their answers versus being limited to checking a box.

Tell people exactly how the information will be used. Being transparent builds trust.

If you ask for voluntary data or require it of your grantee partners or applicants, explain why.

If you ask for data before or after awarding a grant, explain why.

Consider how you will use the data.

Depending on the level of confidentiality you can offer, certain demographic questions may be perceived as intrusive and cause people to skip questions or stop filling out your survey altogether.

Every piece of data you collect in your survey should fulfill a specific purpose, but this is especially true for demographic data. Be sure that you understand why you are collecting different types of demographic data and how you plan to use them.

Explain why you are asking for demographic data and what you will do with it — internally and externally.

Asking for data about personal information naturally raises questions about why an organization is seeking the data and how it will be used. Be sure you can answer those questions.

For example, the California Endowment writes that the data collected will serve multiple purposes: to help us understand how we reflect the communities we serve, to equip our staff with critical data to better serve the needs of our communities, and to track our progress with our Board and our grantees and communities.

Consider how you will you collect data.

In the data collection survey, the responding funders reported that data is mostly collected via applications, reports, and surveys (89–90%) using online and email questionnaires.

Online surveys are an easy option because the data can be quickly transferred into a database, but consider people’s access to the internet when making this decision. Funders also reported the use of focus groups (65%) as a way of collecting data. Focus groups and conversations are a rich method for gathering real-time, useful data and learning for all while also building networks within the artist community. In a face-to-face situation, it might be easier to assure concerns around how the data will be used.

Commissioning research is another option if you are trying to track specific information and want to work with those who have specific analytical skills for evaluating information.

Table 1. Responses to SFIA Survey

How do you collect data? (Check all that apply)

Questions to Explore When Preparing Surveys and Demographic Forms

When beginning to design your data collection methods, we urge you to consider not only what types of questions best capture the range and diversity of folks in your own community, but also what types of questions support field building opportunities in terms of data sharing or survey coordination. Ultimately, as a field, the data collected undergirds field-wide research used to map larger funding trends, such as whether grant dollars increase or decrease alongside the prominence of say racial equity discourse or disability justice, to name a few.

Demographic questions should be asked in a way that is as inclusive as possible. Many people have negative responses to checking boxes that are meant to describe their identity, but only offer incomplete, inaccurate, or sometimes offensive options. Two essential notes we recommend are:

If using an online survey, select the option to shuffle the order in which the options are displayed to avoid the appearance of hierarchy.

If you find that many of your users are filling in the blank with the same thing not offered as a checkbox option, consider offering that as an additional checkbox option on future forms.

Ways to ask about cultural heritage, race, or ethnic identity:

Do not put people in the position of having to fit themselves into a box that is not true to who they are. If you are trying to align your data with Candid, the Census, or some other large data collector for purposes of comparison, you might find yourself in a position of using categories that are not quite a fit for your artist communities. In addition to using broad categories, provide a text box for people to expand on the check box identity marker. Sometimes people are more responsive to checking a broad category box if they can further clarify.

With this in mind, avoid using the word “other” to identify a fill-in-the-blank question wherever possible. Systemic oppression operates by othering folks constantly, making people feel out of place or abnormal. Instead, consider “prefer to self-describe” as this ensures the opportunity to contribute information not available on the list without the value judgment.

Many organizations are moving away from asking people to identify by race and are instead asking about cultural heritage. Since race is a limited social construct, not a biological reality, the continued use of racialized language perpetuates the organization of people by skin color.

For example, the Census Bureau is not using the words “race” or “origin” at all. Instead, the questionnaire may tell people to check the “categories” that describe them. In the agency’s research, many respond with confusion around the term “race” as separate from “origin.” A focus group found that some think the words mean the same thing, while others see race as meaning skin color, ancestry, or culture, while origin means the place where they or their parents were born.

Candid’s ethnic group descriptions:

Indigenous peoples

Multiracial people

People of African descent

People of Asian descent

People of Central Asian descent

People of East Asian descent

People of South Asian descent

People of Southeast Asian descent

People of European descent

People of Latin American descent

People of Caribbean descent

People of Central American descent

People of South American descent

People of Middle Eastern descent

People of Arab descent

As noted previously, categorizing has limitations. In some grantmaker’s surveying, more detailed and specific approaches are taken to understand the nature of racial, ethnic, and/or cultural heritage identities.

For example, the Jerome Foundation expands beyond Indigenous peoples to include Native America/First Nations at the request of Native American artists in the US that do not identify as Indigenous. We also invite responders to share specific ethnic and national groups, and tribal/band affiliations with which responders identify. For example, an artist might check Native American/Indigenous/First Peoples and then specify Ojibway, Turtle Mountain or Winnemem Wintu Tribe, federally unrecognized; or might check European descent, and add Scots/Irish from Appalachia; or might check Multiracial, and add Honduran and Garifuna or Azeri/Persian and Singaporean Peranakan Chinese, etc.

Additionally, arts grantmakers working with the diverse range of racial, ethnic, and religious identities in the geopolitical region often referred to as the “Middle East” have moved beyond this colonial terminology opting for more expansive, inclusive, and self-determined identifiers. The Building Bridges Program at the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation has been using Muslim, Arab, South Asian (MASA) to better capture the unifying racial/ethnic factors in this expansive geography. In their AMEMSA Fact Sheet,1 Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders in Philanthropy (AAPIP) shares research behind their decision to use Middle Eastern while also challenging its imperialist origins. “AMEMSA is a political identity construction grouping Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim, and South Asian communities together under shared experiences, and to build collective power. Other terms exist to position these groups and the region, such as MASA (Muslim, Arab, South Asian), SWANA (South West Asia and North African), and AMSA (Arab, Muslim, and South Asian).”

Queer women of color media arts project (QWOCMAP) racial and ethnic descriptions:2

Are you of Latinx origin?

Yes

No

If you are of Latinx origin, are you:

Indigena

Afrodescendiente

With which of the following regions do you identify in terms of race, ethnicity, and nationality? Please check all that apply.

Southwest/West Asia

South Asia

Central Asia

Southeast Asia

East Asia

Southern Africa

Central Africa

East Africa

North Africa

West Africa

African Descent/Diaspora

First Nations/Native American/Indigenous (the Americas)

Caribbean

Central America

North America

South America

Oceania/Pacific Islands, Hawaii

White/European Descent

Please note specific race, ethnic, and national groups, and tribal/band affiliations with which you identify (i.e., Iranian and Azeri/Persian, Honduran and Garifuna, Singaporean Peranakan Chinese Teo Chew/Hokkien, Chiricahua Apache, Quechua, Purepecha, etc.)

Ways to ask about gender and sexual orientation

Gender

If you are asking respondents about their gender, asking them to select the binary “Male” or “Female” excludes respondents who do not identify as either male or female. What’s wrong with these categories? They assume that gender is binary, that people only identify as one of two genders, which simply is not true. A list of options that includes “Male, Female, or Transgender” is also exclusionary because it presents “transgender” as a category of gender distinct from “male” and “female,” which is also not accurate. Trans women are women no less so than cisgender women are, and trans men are men no less so than cisgender men are.

First clarify why you are asking about gender. Ask the question or questions that meet your needs and ask in a way that communicates respect and understanding.

The Human Rights Coalition (HRC), in an article about collecting demographic data in the workplace, recommends following a 2-part question to allow respondents to select or provide a gender followed by their transgender status. HRC defines “transgender” as an umbrella term that refers to people whose gender identity, expression, or behavior is different from those typically associated with their assigned sex at birth. Other identities considered to fall under this umbrella can include non-binary, gender fluid, and genderqueer — as well as many more.

What is your gender identity? (select all that apply)

Fa’afanine

Genderqueer/gender non-conforming

Hijra

Intersex

Mahu

Man

Muxe

Nadleeh

Two Spirit

Woman

I describe my gender identity in another way (please describe)

I decline to state

Do you identify as transgender?

Yes

No

I decline to state

Importantly, when drafting survey questions inclusive of trans identifying folks, understand the precarity many folks in this community face.

There are risks many trans people face when cis people learn that they are trans. Bias against transgender people in the United States is often extremely harsh, and trans people experience very high rates of violence and discrimination. Working to be more inclusive in how we ask about gender and how we protect the privacy of this information is a small but important part of working to end discrimination against trans people.

Sexual Orientation

Questions regarding sexual orientation are distinct and separate from Gender Identity. Response choices need to be inclusive and capture the scope of orientations including heterosexual or straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, and an option to describe an additional sexual orientation.

With which of the following sexual orientations do you identify:

Asexual

Bisexual

Demisexual

Pansexual

Queer

Same Gender-Loving

Two Spirit

I describe my sexual orientation or identity in another way (please describe)

I decline to state

When considering collecting data on gender and sexual orientation, people often worry that respondents are more likely to skip these questions. Researchers at the Census Bureau conducted an experiment to see whether respondents were more likely to skip SOGI (sexual orientation and gender identity questions) than typical demographic questions. They did not find evidence for that at all; in fact, significantly more people skipped the question about income than the question on sexual identity.

Pronouns

Knowing an individual’s pronoun provides respectful information to avoid mis-gendering a person. A common objection or concern that arises when pronouns are presented is the notion of “incorrect grammar” when using they as a singular pronoun. If you are concerned that using “they” to refer to an individual is grammatically incorrect, consider prioritizing the needs of human beings to feel seen and respected over the needs of a dictionary — written and upheld by dominant culture, often meant to separate peoples on the basis of assimilation into White dominant culture — to remain consistent over centuries. Language evolves all the time. We can make room for everyone.

Please identify your pronouns: (select all that apply)

He, him, his

She, her, hers

They, them, theirs

Sie/Ze, hir, hirs

Pronoun Flexible

Prefer to self-describe

Ways to ask about disability and accessibility

Across the United States, when speaking about disability, people-first language has largely taken hold. This has been adopted widely as it is considered both respectful and the most appropriate way to refer to those who were once called by derogatory terms, such as handicapped or even crippled. People-first (or person-first) language does just that. Person with a disability instead of disabled person, person with autism instead of autistic person, and so on. This approach not only centers the person themselves, but also creates a sharp separation from previous terminology that originated from incredibly negative, discriminatory, and inequitable societies.

People-first way of asking about disability:

Are you part of the disability community?

Yes

No

I decline to state

Increasing in use is identity-first language, largely due to the persistent efforts of the disability justice community. Though person-first language is designed to promote respect, the concept is based on the idea that disability is something negative, something that one should not see.3 As Cara Liebowitz writes in her essay for The Body is Not an Apology, “Identity-first language is founded upon the idea of the social model of disability. In a nutshell, the social model says that though our impairments (our diagnostic, medical conditions) may limit us in some ways, it is the inaccessibility of society that actually disables us and renders us unable to function.”4

Some arts funders use the identity-first approach in demographic survey questions, such as Dance/NYC, who have been working extensively with folks in the disability arts community.

Identity-first way of asking about disability:

Do you identify as:

Disabled person

Nondisabled person

I decline to state

It is important to state, whenever surveying about disability, never ask for an individual about the origins of their disability or require identifying a type of disability. If the nature of your inquiry is to understand what types of accommodations may be necessary — as both physical and virtual environments are not designed inclusively for all types of access — consider asking about accessibility needs and/or accommodations.

Do you have any accessibility needs (ASL interpretation, CART, etc.)? If yes, please explain below:

Yes

No

Ways to ask about age

The best way to ask about age is with a simple multiple-choice format that uses age ranges for each answer. Some people may not feel comfortable revealing their exact age, so this structure allows them to participate while still protecting their personal information.

It is important to let people know directly if there are any age requirements involved in your program or activity.

What is your age range? (adjust according to your needs and the age groups with which you are working)

Under 25

25–34

35–44

45–54

55–64

65–74

75 or older

Decline to state

TABLE 2. Demographic Data Collected from Individual Artists Grantmakers

From who do you collect data? (Check all that apply)

How do you analyze data?

The importance of data in the arts and culture sector cannot be overstated. Landmark reports like Helicon Collaborative’s “Not Just Money” have challenged the philanthropic sector to critically engage with its lack of progress on equity within arts funding. Others, like Americans for the Arts’ “Arts & Economic Prosperity Reports” have advocated for the value of the arts and culture sector articulating its impact in economic development terms, providing data on its contributions towards job creation, government revenue, and tourism. And even GIA’s own annual “Arts Funding Snapshots” provide useful baselines tracking important sector trends in public and private grantmaking. These reports, and many others, highlight not only the importance of data collection in and of itself, but how necessary the analysis and interpretation of that data is to the validation, relevance, and evolution of our field. In his introduction to GIA’s “Arts Funding at Twenty-Five,” author Steven Lawrence underscores this importance stating, “The contemporary ease in accessing reams of data now regularly reminds users … that numbers without thoughtful interpretation can be at best meaningless and at worst intentionally misleading. The creators of the first Arts Funding study had the foresight to know that how these new data would be analyzed and explained would be equally important in determining their ultimate value to arts and culture philanthropists and the sector as a whole.”

As such, the SFIA Committee felt it was important to better understand who fills the critical role of data analysis and interpretation within GIA members’ institutions and what supports might be most useful in this work. The survey revealed that it is in large part internal Program Staff who are responsible for evaluating and interpreting data. While this group comprised approximately 95% of respondents, the survey also found that outside consultants (36%) followed by funder executives and boards (32%) also do this work. Approximately 11% of respondents selected “Other,” offering specific roles such as “impact and assessment managers,” “research and evaluation staff,” and “executive director” as examples of who within their organization is tasked with this work.

While comments surfaced that some members have teams dedicated to data evaluation and interpretation, other respondents shared that staff responsible for this work do not have specific skills or training in data analysis. Others shared that their institutions were in the process of creating specific positions to lead these efforts, and some even shared their challenges with thorough data analysis without dedicated staff. Respondents also lifted the need for expertise in analyzing and interpreting quantitative and qualitative data. This led the committee to consider what opportunities there may be to share methods and tools among members and whether there is a need for training of program staff to more effectively evaluate and interpret data their institutions are collecting.

As a beginning, we reached out to several experts for their advice to those responsible for this work and recommendations on helpful practices, resources, and tools. Below is a summary of their responses to the following questions:

Are there key resources you would recommend to staff dedicated to data analysis and interpretation?

What key considerations/field standards should those responsible keep in mind in data analysis and interpretation?

Are there best practices you would share with this group, especially as it relates to equity centered data analysis and interpretation?

What advice do you have for staff that may not have specific training in data analysis and interpretation but are responsible for the work?

Training

Data analysis is a skill that requires training. However, you do not have to be a statistician to analyze data. Identify what basic training you need and when resources allow, advocate for dedicated staff with this expertise to lead this work. If the data you’re collecting is more complex, identify what outside expertise you need.

If you do not have the resources to hire a consultant or dedicated internal staff, consider what existing resources that may already exist or training opportunities that will deepen the skills necessary to do this work:

For those working in public agencies, inquire about what other departments may have this expertise and if training opportunities may be available;

Explore extension programs at local colleges or universities; and

Explore online trainings in tools you may use to analyze and interpret data like Excel, Tableau, etc.

Data Collection: Before you start

Data collection — be it a survey, interview, or focus group — represents valuable time and resources from your constituents that takes them away from their core work. When you are able, compensate participants for their time and expertise if solicited.

Be transparent about what you plan on doing with the data and communicate how it will be used in decision making or other processes that may impact your constituents. Build in opportunities for feedback along the way.

Before you launch into a data collection effort, ask yourself the following questions:

Is the answer to the research question actionable?

Is my organizations planning to act on the results we receive?

What data do I need to answer the question I have right now?

Do I already know what the findings would tell me?

Is there an existing body of research that answers my question? If so, what questions haven’t been answered? How can I complement and build on existing research?

Too much or too little

A critical consideration that researchers pointed out was the importance of having focused research questions. Clarify what data you really need to answer your question. When you are collecting data or tasked with doing so there is a tendency to collect too much by asking for everything. This can be counterproductive and unsustainable, especially when you do not have the mechanisms to do collect data and put it to use. This often results in short bursts of data collection activity and can cause fatigue from constituents and may undermine your future efforts. Instead, start small and ask concrete questions that have a clear focus — ask yourself what data you need to answer the question you have right now. This will enable you to make the data actionable, help build the case for its utility, and will be easier to communicate out about to your constituency.

At the same time, do not narrow down your parameters so much that you find yourself comparing individuals and not groups. Right-size your data collection efforts so you that you can arrive at statistically meaningful, actionable results that can inform your work.

Be purposeful, detailed, and consistent in your data collection efforts. Some considerations to keep in mind:

When collecting demographic data, consider if it would serve your purposes to have a comparative data set, like census data, and structure your questions to either replicate or roll up into that other data set. While problematic in the identification categories it offers, the census provides demographic data across the entire country, and everyone has access to it.

Be sure to structure your questions to go as deep as you need in a way that respects and acknowledges the complexity of your community. Always provide a field for respondents to self-identify. These responses can often illuminate parts of your community that are not often visible and/or require an intersectional lens. This can especially be true when asking questions about gender and sexuality.

There will always be a lag between the speed of research and the evolving ways of how communities self-identify. Consider acknowledging this gap on the front end in your communications to participants.

Think Ahead! consider how to be consistent in how you collect data so that you can analyze it longitudinally.

Choosing Your Methodology

Select the appropriate methodology and acknowledge the type of data it can solicit. For example, surveys may be appropriate for gathering numbers but, for more nuanced information, interviews or focus groups may be more effective. Consider utilizing a mix of methodologies depending on the information you need.

Clarify what data you really need and construct questions that will inspire participants to answer them honestly. When asking subjective questions, be aware of how they may be leading and affirming your own assumptions. Be aware of the biases associated with the methodologies you select and who may or may not participate in your data collection efforts as a result. For example, consider when a written survey accessed online may provide different results than interviews conducted in-person or by phone.

Be open to letting data tell you a story. For example, offering an opportunity for participants to self-identify their artistic practice on a survey may yield important information on emergent disciplines in the field.

Interviews

While interviews can be time consuming and resource intensive, they can often yield rich, critical information that you would not be able to gather otherwise. When using this methodology consider the following:

Do you have the trust to collect the data you need?

Is there a trusted peer who can conduct the interviews?

Is a clear interview process established?

Is confidentiality a core principle of the process?

As a funder, you may consider conducting interviews yourself. If this is the case, begin by identifying grantee partners with whom you have a long standing relationship. This will likely help you receive more accurate responses. Also, acknowledge that there is a power dynamic no matter the nature or length of the relationship. The information you receive will be biased. When analyzing results from interviews, look for patterns and anomalies across responses. Let these findings inform your recommendations. If possible, have others review your analysis and solicit feedback.

Focus Groups

Focus groups are another methodology to consider. When folks are in conversation with others they know it often results in more transparent dialog. If conducting a focus group, consider:

Identifying an external person with expertise to manage the focus group;

Having the facilitator reflect the individuals of the focus group which can engender further trust and transparency, such as being from a similar background or community;

Designing a well-structured process; and

Making sure you are documenting the process fully and effectively.

Metrics

Do not marry yourself to the metric alone. While identifying metrics is critical to assessing progress, they can sometimes be a distraction from your ultimate goal. As an example, Harvard University has been working towards building a more diverse student body. However, while the student body may be more racially diverse than in prior years, a 2018 article reported that the university had not made progress on the socio-economic diversity of its student body. Progress on one metric does not tell the whole story. Be open to changing or adapting your metrics if they are not moving you closer to your larger goal.

Anecdotal Data

Acknowledge the “informal” methods you may be employing to gather data, like participant observation. For example, attending grantee events or performances can be opportunities to gather data on the communities served and the value the program/organization holds within the community directly from participants. While the data is anecdotal, it is no less relevant.

How to Think about Data Privacy and Security

Fostering Trust through Information Management

Engendering trust among funders and grantees is key to the foundation of a healthy and mutually rewarding professional relationship. Successful funding partnerships invariably rely on a set of principles and practices that are meant to uplift shared aspirations and expectations. While opportunities to foster trust are bountiful and are embedded in many facets of the relationship-building process, the findings below will focus on the role that data management plays in the preservation of trust. Responsible data management will be explored from the discovery phase, which will address trust issues that arise based on the type of information being solicited, and the management phase, which will delineate how data is technically processed and handled from a security perspective/standpoint.

TABLE 3. Responses to SFIA Survey

With whom do you share data? (Check all that apply)

Security and Data Sharing

We asked funders to share their approach to data security management. The question was a narrative prompt, allowing respondents to interpret the following question based on their direct knowledge of the subject: How are you addressing data security? Please explain. While the answers varied in detail, three patterns emerged: [1] reliance on security measures from outsourced data management providers; [2] security managed by internal IT department or government regulation; and [3] in-house and cloud-based servers. Other methods indicated the use of written security protocols, limiting requests for sensitive information, restricting personnel access to information, and using strong passwords. Four respondents noted an inability to answer the question. Similarly, there were a couple of requests to provide guidance or training on the subject matter.

Accountability and transparency are key considerations for the distribution of data. With respect to data sharing, funders noted that information was viewed mostly by staff (94%) and board (77%). Only 20% of funders share data with applicants. Respondents underscored the importance of instituting ethical processes for determining which data can be shared with whom. Funders who share data with the public indicated that they do so in aggregate form, while some public agencies are beholden to state transparency laws. For example, the following message might be shared prior to a survey being administered:

Individual-level data is never shared. If organization-level data is shared, it is anonymized. We have a Quality Assurance policy that sets parameters for how data is shared, and we follow ethics guidelines and best practices for the protection of human subjects. We are part of the County’s Open Data Task Force, and wherever possible we post data related to our programs and services on the Open Data Portal.

Stewardship

By nature of the transactional relationship, a partnership between funder and grantee is infused with an asymmetrical power dynamic at the onset. Simply put, the funder has resources that the grantee needs. In exchange for the resources, the funder gathers information from its prospects to assess a suitable match, contextualize the work within a broader framework, conduct comparative analyses, measure impact, inform future programming, deliver funding support, and report to its authorizers. The sensitivity of gathered data can vary from personally identifiable information to aggregate and anonymous data. Whatever the case may be, mindful harvesting and handling of data is essential to building and preserving trust among stakeholders.

Stewardship begins at the conceptual, data design phase. When preparing a data collection project, Foundant Technologies recommends centering data within a triangle framed by three categories: people, technology, and processes. Each category involves a simple set of questions that reveal the depth and breadth of procedures necessary to responsibly manage the project. The following self-guided assessment can set the stage for responsible data gathering.

Data design5

What data does your organization collect? Consider the purpose for collecting data and determine the least amount of information needed to gain accurate, timely, and relevant statistics. Consider if the necessary information is already available elsewhere and right-size your query accordingly. Consider purpose, data integrity, bias, how is data evaluated for use in an appropriate and responsible way, be clear on what the data will and won’t represent, ensure consent and transparency for collecting and using data. Co-design questions with the intended audiences to be inclusive, transparent, ensure diversity of perspective, and promote participation.

Is it all necessary? If you are collecting personally identifiable information, do you de-identify the information as it moves along the process? Does any of the information put your constituents at risk? How do you ensure security throughout the process?

What is the data lifecycle? Consider the timeline from input to close of project. How do different iterations of the data (print and digital) flow through the organization: technologies, staff, and stakeholders?

How long is it kept? How long is the information relevant? Should it be archived or disposed?

Who can access it? Consider limited or layered privileges needed for designated staff to adequately do their job.

Is it encrypted? What measures are in place to ensure integrity, privacy and security of the information?

Is it backed up? Is the information backed up on a cloud, on a server, through a service provider, or in-house storage? Are different iterations of the information tracked for integrity?

Where does it live — can you diagram the data flow in your organization? Organize how the data will flow through your agency to assess the appropriate permissions and security protocols along the way. How secure are the applications used to process data (excel, online collaborative tools, third party platforms, etc.)?

Technology7

What devices does your organization allow/support and how are they connected (diagram)? Determine the safest way to intake and process information. Are you using third party platforms? Are you using personal and/or company mobile devices and/or computers?

What security measures are in place for each device and for the transfer of data between devices? (encryption, password protection, double authentication, antivirus, firewalls, MFA, security updates, etc.)?

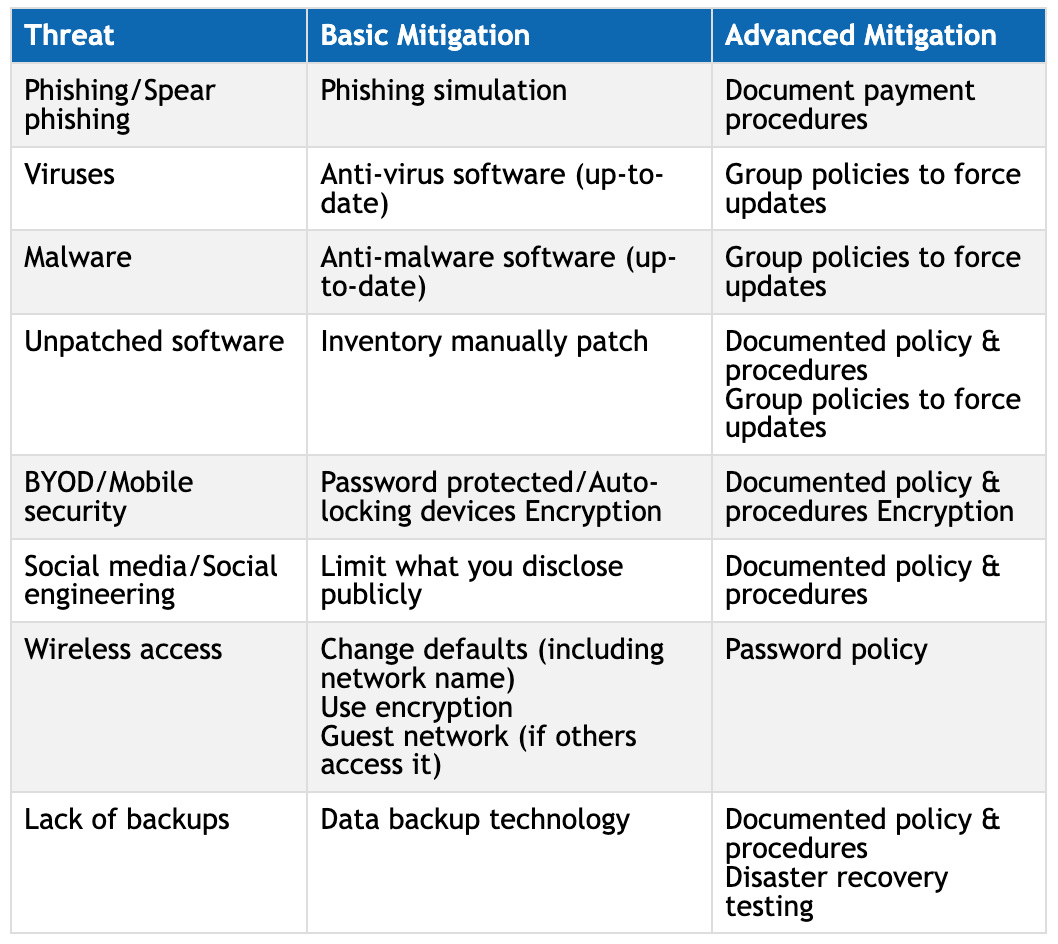

TABLE 4. Security Threats, Mitigation Data, and You6

People (roles, access, etc.)

Who can access what data and for how long? Assign minimum permissions to do the job. Consider all persons handling the data throughout its lifecycle (interns, consultants, program officers, board members, marketing, etc). A system of checks and balances can preserve the data’s integrity, security, and privacy, while allowing prompt access to information as needed for accountability and transparency.

Who is ultimately responsible for protecting the data? Who can respond to security questions?

Processes

Onboarding: Create an initial security awareness training to onboard personnel. Outline the responsibilities, guidelines and security protocols for managing data.

Training: Determine necessary training to ensure integrity, accuracy, and protection of data. Review permissions allowable for viewing, editing, transferring, and communicating data sets. Outline measures for addressing security issues.

Role transition: Ensure permissions and access to data and devices are properly redistributed and redefined.

Technology acquisition/disposal: Create a process for securing new devices and software applications, as well as a process for deleting information on devices and platforms that will be deaccessioned.

Incident response: Create a process for addressing security issues. Table 3 offers some guidance for mitigating risks.

NIST password requirement basics8

Length: 8–64 characters are recommended.

Character types: Nonstandard characters, such as emoticons, are allowed when possible.

Construction: Long passphrases are encouraged. They must not match entries in the prohibited password dictionary.

Reset: Required only if the password is compromised or forgotten.

Multifactor authentication: Encouraged in all but the least sensitive applications.

For funding institutions working to improve the lives of the artists they work with, secure access to personal information may be essential to deliver customized programs and services based on their constituent needs. The ability to analyze these data sets over time also provides funders an insightful platform to further understand and contextualize the communities they serve within a broader framework. With this degree of access, grantmakers share a deep responsibility to be conscientious stewards in their data collection practices. The spectrum of accountability includes the secure flow of information from the onset of design, to the intake platform, user permissions, storage, distribution, and deaccession. Implementing security protocols for each stage of the process is instrumental to protecting stakeholder’s privacy and preserving their trust.

Many thanks to the GIA Support for Individual Artist Committee for their contributions to the design and completion of the survey that provided data for this report.

Contributors and Writers include: Allyson Esposito, executive director, Northwest Arkansas Council, Arts Service Organization; Adriana Gallego, executive director, Arts Foundation for Tucson and Southern Arizona; Adriana Griño, program officer, Kenneth Rainin Foundation; Brian McGuigan, program director, Artist Trust; Eleanor Savage, program director, The Jerome Foundation; and Sherylynn Sealy, program manager, Grantmakers in the Arts.

Additional research support from Anh Thang Dao-Shah, director of Equity Strategies and Wellness - Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center; Alexis Frasz, co-director, Helicon Collaborative; and Laura Poppiti, grants program director, Center for Cultural Innovation.

Editing support from Suzy Delvalle, president & executive director, Creative Capital and Nadia Elokdah, vice president & director of programs, Grantmakers in the Arts.

Infographic creation and design by Heba Elmasry.

ENDNOTES

Asian Americans Pacific Islanders in Philanthropy (AAPIP) AMEMSA Fact Sheet, November 2011. Accessed July 12, 2020. https://aapip.org/sites/default/files/incubation/files/amemsa20fact20sheet.pdf

Queer Women of Color Media Arts Project (QWOCMAP). Accessed July 12, 2020. https://qwocmap.org

Cara Liebowitz, “I am Disabled: On Identity-First Versus People- First Language,” The Body is Not an Apology, March 20, 2015. Accessed on July 12, 2020. https://thebodyisnotanapology.com/magazine/i-am-disabled-on-identity-first-versus-people-first-language/

ibid.

Foundant Technologies, Data Security, Foundant, and You, https://resources.foundant.com/education-webinars-for-grantmakers/data-security-foundant-and-you-4

Ibid.

Ibid.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), “Digital Identity Guidelines,” NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-63-3,” USA, June 2017