Reflections on Anti-Racist Experimentation in a Public Arts Agency

The challenge of radically interpreting systemic racism as production of racial capitalism

Daniel Singh and Justin Laing

MAKING AN ANTI-RACIST COMMITMENT

“You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.”

When Daniel applied for the Metro Arts position in February of 2022, he was heartened that the commission had a Committee on Anti-racism and Equity (CARE) and was excited when he began his tenure. Early in his time at Metro Arts, there was a joint meeting with the full commission and CARE to chart the path forward. At the first meeting, CARE had the option to choose incremental DEIA work or address systemic inequities with anti-racist practices. In October 2022, the group collectively chose to move forward with an anti-racist approach to address the historic harm created by Metro Arts. With this anti-racist mandate from October 2022, Daniel began assembling a team that would help Nashville make the task at hand possible.

ASSEMBLING A TEAM/DEFINING TERMS

Feeling concerned about the complexities, Daniel initiated a disparity study with RISE Research and engaged Justin Laing, of Hillombo LLC to help create an anti-racist path forward and implement the ongoing ask of CARE to demonstrate with evidence that we are addressing racism head-on in our work. Justin uses a blend of Adaptive Leadership, socialist/Black Radical Tradition, and critical race frameworks in supporting a team to create anti-racist experiments. In this case that included engaging staff, commission, grants-editing panels, and artists in the community to develop an experiment intended to significantly shift resources to BIPOC artists and arts organizations. “Socialism” in this case is a reference to the framework of non-reformist reforms of Andre Gorz and the attempt to build the opportunity for democratic control over the economic workings of an organization, disrupt Whiteness and BIPOC professional class participation in reproducing racism while under racial capitalism. Racial capitalism, a term explained and made popular in the U.S. by Cedric Robinson in “Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition”, is to say a racial ethos and practice rooted in traditions of Greco/European people that justifies and guides the distribution of resources under capitalism according to a racial, national, and gender assignment that is ultimately intended to reproduce the White ruling classes.

These experiments are built on criteria defined as anti-racist, one of which is the need for narrative reframing that names the role of White capital classes in the arts, as well as historical ways arts have facilitated the reproduction of European supremacy such that fairness requires redistribution of resources. The reframing was instrumental in creating arguments to shift resources and power and helped to build a coalition of support, but it also signaled the arts forces aligned with capital classes and the State (patron-class arts organizations or arts organizations that were formed by patrons and not working artists) to actively mobilize against the work we were wanting to do for BIPOC working-class artists and organizations.

Adjusting Justin’s terms with the invitation to adapt them to our situation and hopefully lower the levels of tension, with Dana Parsons facilitating Daniel and staff arrived at three priorities in their framing of anti-racism: Transparency, Right Distribution, and Power Shift in April 2023. One of the principles used was Critical Race Theory’s Material Determinism or the idea that White Institutions will not benefit Black people unless they see it to be in their material interest and this was connected to the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond’s instruction that undoing racism requires accountability. As we moved further along our anti-racist work and were still not able to garner support with terms designed to be less conflictual, we returned to the frameworks Justin offered and these became “narrative reframe”, “democratization of processes” (more community members deciding the distribution), and the “shifting of power/resources to people of the global majority.”

CENTERING THE VOICES OF THE BIPOC ARTISTS

We brought in the artists and arts organizations who previously had faced prohibitive barriers from applying and centered them in our work. With community-led editing processes, we worked through simplifying our funding applications and making them more accessible to communities that had faced prohibitive barriers from applying. Simultaneously, we began having intentional conversations with staff, CARE, and community stakeholders such as organizers like Elmahaba Center, Black Nashville Assembly, North Nashville Arts Coalition, and Liberated Grounds to name a few. Through this work, we created a short-term approach to making accessible the existing funding pathways while also moving forward on longer-term anti-racist approaches that are yet to be implemented. The short-term approaches prioritized communities previously unable to participate in Metro Arts funding. As part of our attempt to make these shifts, Metro Arts committed to the principle that no existing grantee would lose funding in the following fiscal year to counter the resistance from the white capital class commissioners and arts organizations. In retrospect, this was a mistake–using a somewhat naive framework of “both/and” and avoiding a “scarcity mindset” we were promising an outcome designed to keep White arts organizations “at the table”. When additional resources were not available and BIPOC artists were centered, most White arts organizations left the coalition and this earlier commitment was used as a loophole to return to the prior funding arrangement. We are terming this a “loophole” because as was mentioned in the public hearings by Commissioners, the Commission had no problem not adhering to the eight years of equity commitments it had previously made. This was made more egregious because of the RISE Research report that portrayed historic disparities in arts funding between capital-class White and artist-based BIPOC organizations in Nashville. As we processed the outcome, we agreed that there is a conflict over resources among arts organizations and artists that breaks out along, political orientation, genre, racialization, class, and gender and the conflict needs to be acknowledged at the outset of the work because the endemic conflict that is present in the community will present itself in the arts as well.

INTERPRETING OUR WORK RADICALLY: THE TOUGH CHOICES OF WHITE SETTLER & PROFESSIONAL CLASS BIPOC PEOPLE

The earlier disparity study informed us that the funding and support of BIPOC organizations was so large that it couldn’t even be measured per the current judicial precedent. Our data review pointed out that 88% of our previous funding had gone to patron-class arts organizations e.g. organizations that were not begun by working artists, but rather by patrons, and these were typically white-led and majority white-serving, eurocentric organizations. Given these data points, in July of 2023, the Arts Commission voted to prioritize BIPOC artists and communities that had met the standard of quality as determined by the grants review panel. However, a Commissioner who had a working relationship with some of the patron class organizations introduced the most recent Supreme Court ruling on Affirmative Action as a reason to undo the July 2023 vote. The commission voted again in August 2023, and this time decided to keep the status quo of funneling taxpayer dollars back to the patron class organizations.

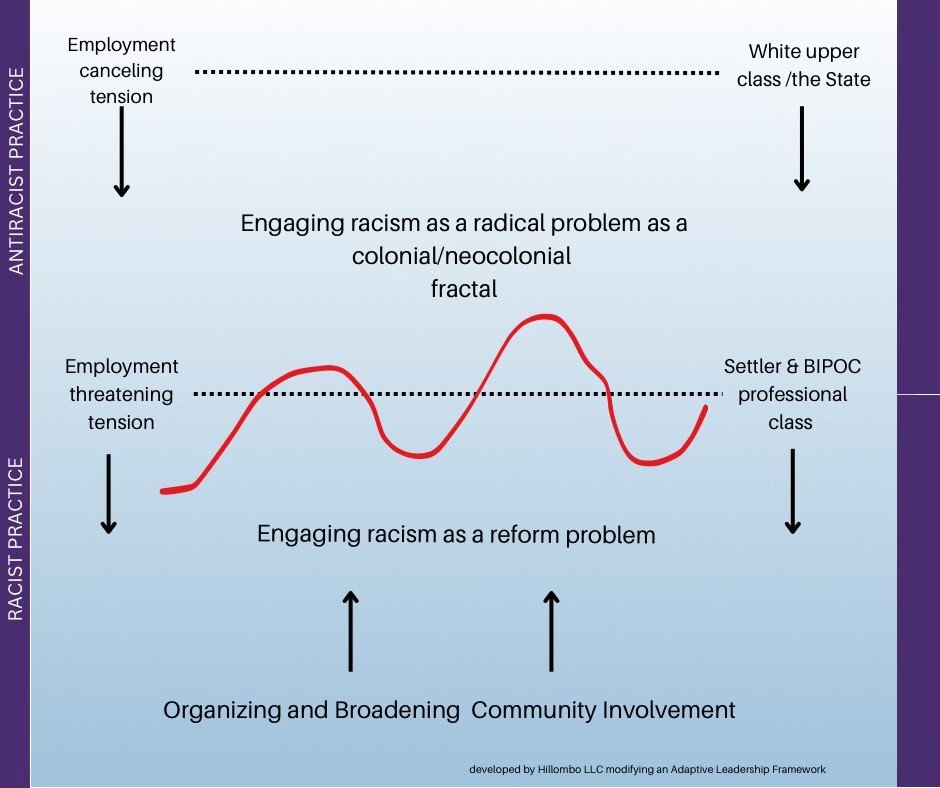

Figure A: Illustrated model, developed by Justin Laing, modified from Adaptive Leadership and Emergent Strategy models.

In the modified Adaptive Leadership model Justin uses (see Figure A), we had gone through the level of loss tolerated by White settler and BIPOC professional classes and they had in turn responded to limit that loss to a size they felt acceptable.

In the image, the red line represents the experiment. It is proposed that the tension the experiment causes will need to go above and below the line between interpreting a problem radically and in a manner of reform for the person or team leading it to have a chance to both shift narratives and resources to BIPOC people and keep their job, contract, or grant. The figure tries to make the point that when we interpret an issue with the intent to create a reform, we are, ultimately going to reproduce the problem, although our job is safe and when we interpret and act on it radically, as a subset of the larger system of racial capitalism, for example, then we will have the chance to disrupt the reproduction of racism but our class position will be at risk. As a result, any change will come from “the bottom”, e.g. BIPOC artists organizing on their behalf and possibly seeking support from administrators willing to put their jobs at risk.

THE ARTISTS ORGANIZE

In the Fall of 2023, artists organized a collective, Arts Equity Nashville, and filed a grievance with the Metro Human Relations Commission (MHRC) alleging that a Title VI violation had occurred in the August vote and that the Metro Arts Commission and Metro Legal had acted in a racist manner. This was based on the strong work of the anti-colonial/anti-capitalist frameworks that the Nashville Arts Equity established as one of their tenets. Despite Metro agencies attempting to prevent/slow down the MHRC investigation, Rev. Davie Tucker and his Policy Director Ashley Bacheldor undertook a deep review of the processes at Metro Arts Commission and engaged an attorney Mel Fowler-Green for a legal opinion. On March 4, 2024, MHRC found that Metro Legal and Metro Arts had violated Title VI and recommended that the Arts Commission move back to the July 2023 vote or find a way to make whole the artists whose funding was revoked since that vote. The MHRC report and the legal brief outlining how and when race can be one of the factors of decision-making with taxpayer dollars is available here.

Today, Daniel is on FMLA and Metro is resisting making the artists whole or allowing Daniel to return from his FMLA leave.

However, all was not lost and we would like to point out the following significant moments organized around 1) power shifts, 2) found retractable resistance, and 3) closed with some recommendations.

POSITIVE TERRAIN SHIFTS

We gained increased clarity around what we meant by the term anti-racism and the need for greater power mapping as the work commences: In April 2023, staff identified these three anti-racist priorities: Transparency with a narrative reframe, Democratization of processes, and Shifting resources to previously harmed communities.

Local artists organized themselves and successfully:

Redirected a $2M earmark for large organizations towards an open application process.

Hosted a mayoral candidate forum where all the candidates committed to 1% of the combined general and educational budget for the arts.

Filed a successful Title VI violation grievance with MHRC and received a finding that there indeed was a violation and they should

Continue organizing and building coalitions around the larger work of systemic change with an analysis based on anticolonial, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist frameworks.

As a tangent of the MHRC grievance, the agency gained prominence and support within Metro Nashville and nationally.

Making the Metro Arts program more visible to the larger community

Shifted funding formulas and simplified funding applications to prioritize communities previously harmed by Metro Arts.

Increased access by bringing in 175 individual artists through the Thrive program and 88 Operating Grant applicants in the first year since the formula change.

Increased applicants to 201 in Thrive and 109 in Operating Grants in the second year.

National recognition: recognized by NEA/White House with an invitation to their Summit on “Healing, Bridging, and Thriving,” and Grantmakers in the Arts, etc for the work we were doing in Nashville.

Coalition Building Outside of the Arts: Daniel focused on building coalitions with folks on the ground working in the anti-racist space already and learned from their work. Some of these local leaders include: Black Nashville Assembly, Elmahaba, Liberated Grounds, North Nashville Arts Advocacy Coalition

Building the case: We completed an attempted Disparity Study to look at our historic funding approaches. We completed a Comparison Study to look at how the Metro government was funding the greater Nashville artists in comparison to peer localities.

For the first time in our history, Metro Arts funding applications are now aligned with the mayor’s budget timeline to give actual projections to the mayor's office and council.

JUSTIN’S LESSONS

Justin ended up leaving the project early as there was not an agreement to conduct anti-racist cultural planning, the Commission was suggesting that resources were scarce and staff was not aligned with the work. One of the realities that were only deepened for Justin from this experience is that, unfortunately, anti-racist work e.g. work attempting to shift narratives and material resources from White capital-class supported arts organizations, genres, and artists to working-class BIPOC artists and arts organizations, particularly while working in State entity, will almost immediately bring one’s job/contract/funding into a place of tension or risk. The way that power is arranged in cities and the deep connections capital-class arts organizations have through their boards and staffs to the funding structures means that changing power relations may have to receive a lot of attention before resource change is attempted. Of course, trying to build the power of BIPOC arts organizations and artists is likely to be difficult from the seat of a funding organization since it is claiming to be neutral. So, it may be that this work has to be led by artists on their own, which of course brings back the job/contract/funding risk mentioned above.

Another challenge may be that as the arts and artists have been framed as apolitical spaces of beauty or the imagination, acting politically is not the kind of action a lot of artists see as their mode of being. What needs more attention is the idea that arts and politics are distinctly different areas. However, it may just be that “the arts” as a general rule and a system are a place of conservative, reformist politics and so politics that run counter to that norm may feel more risky than is helpful to arts and culture workers already in a precarious economic position. Ultimately, this means that Adaptive Leadership’s notion of “sustainable disruption”, having been normed in White capitalist organizations has limited applicability to anti-racist work or that the kinds of work that are sustainable are harmful in that they represent themselves as anti-racist but is furthering power of White capital classes and the State.

DANIEL’S LESSONS

For Daniel, the situation on the ground started weak and turned even more precarious with more than half the staff gone, having to work with five different commission chairs, and almost a complete turnover of the rest of the commission in the short time he has been in Nashville, potential allies like the Diversity Office feeling they couldn’t speak publicly for equitable paths forward, mayoral/council transition, and no ability to support the artist or similar organizing collectives. There was a lot of goodwill, immense labor by various stakeholders in holding accountable various entities in Metro Nashville, and incredible public service in MHRC’s fact-finding investigation, commissioned legal analysis, and final report recommending funding for the artists who lost it.

While there was all this momentum and effort coming from working BIPOC artists, the professional class, both BIPOC and White, female and male-identifying, used the State apparatus to isolate each attempt through a variety of legal, human resource, and general bureaucratic tactics, so that coalescing and working in harmony to make the impact of our work more coordinated was very difficult. Relatively politically isolated, Daniel’s situation became even more precarious than anticipated. In hindsight, he would have brought on staff 1-2 at a time and would have worked with CARE to align staff, CARE, and commission around their anti-racist frameworks and priorities. Daniel was surprised to see the retaliation and that the staff was not aligned with anti-racist principles. Despite months of audit reviews, nothing concrete has been named as a problem. The HR investigation laid out that the staff tensions were largely around anti-racist versus DEIA approaches to change. The staff has proposed privatizing individual artist awards–thereby putting the most vulnerable individuals of the arts ecosystem at the whims of the patron class philanthropies–the opposite of a social network of support that is built from tax funds. The legal director has hired a lawyer to “assist” HR staff who collectively have over 40 years of experience in helping them with a simple FMLA process–which has had the primary motive of preventing Daniel from returning to work with intermittent FMLA despite submitting new forms multiple times. The isolation is stark as well as complete.

However, anti-racist organizing is always inherently risky and will continue to isolate anyone working in the anti-racist space–our challenge is to build constituencies that move beyond a liberal critique of racism as a problem of inclusion and link the arts to the reproduction of racial capitalism so that we can change the way power is arranged ‘on the ground’. We have the concrete example of the COVID-19 pandemic where it was possible to mobilize large policy changes when we put sufficient efforts and resources to bring about a change like remote work options–something the Disability Community has been asking for and advocating for decades. At the same time, we also saw that the pandemic relief efforts left out large groups of BIPOC community members. The struggle is to keep advancing the work with what we have as tools; understand and re-envision the terrain and strategy, and keep a critical self-evaluation going at all times.

What gives Daniel hope is that the artists are coalescing strongly and working with peer-organizing collectives – hopefully, their wedge against the wall of racism will continue to become more and more coordinated and effective over time. We also want to learn from others working in difficult terrains like Nashville where artists are surrounded by an organized patron class within a conservative state climate. This article is crafted to contribute to a continuing conversation so we can learn together and collectively move this process forward.

RECOMMENDATIONS

These recommendations are based on the current power map an arts administrator might face in Metro Nashville or similar locales. I would always consult with local community organizers to get a sense of what they suggest would be most effective as a strategy. In Nashville’s instance, the BIPOC middle class frequently aligned with the white professional class which was not surprising but still disappointing. What is incumbent on BIPOC arts leaders is to continue to investigate the terrain and risk, commit to organizing, aligning, and learning from local anti-racist leaders, and then organize with local communities for the risks we will take.

Artists' struggles must be connected with other movements like labor, education, housing, and transit. Otherwise, we will splinter and not be able to anchor any changes.

More intersectional approaches such as anti-racism, anti-colonialism, socialism, feminism, queer studies, disability studies, social work, and restorative practices, in the development of public policy as a transition to socialism.

We must imagine radical shifts rather than facilitate the conservative tendencies in the arts that seek to reproduce class and “race” relations through the arts by incremental approaches.

Build a coalition of 5-10 cities that can do this work with you to support each other and serve as peer benchmarks.

Developing financing for artist organizing has to be figured out.

Be prepared for folks to slow-walk you by thinking through your recommendations carefully with fully articulated strategies.

Directors brought in for change must have union or civil service protection with contract language that guarantees support.

Political parties must be scrutinized for their vision of arts and culture and must be measured with clear scorecards on outcomes.

Do not underestimate the time it will take to organize and build a collective vision.

The opposition will fight every step of the way. Be prepared for the long haul, or that you may not be able to stay for the long haul.

CLOSING THOUGHT

A coalition of anti-racist organizers across the arts, education, labor (unions), carceral abolition, and other parallel movements must come together with their practices to dismantle White Supremacy. Working in silos in just the arts sector is not going to bring about the structural and systemic changes we are seeking.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Daniel Singh is executive director of Metro Arts.

Justin Laing is principal with Hillombo LLC.