Community Powered Creative Placekeeping in Santo Domingo Pueblo

Joseph Kunkel, MASS / Native Sustainable Native Communities Design Lab

New Mexico’s Santo Domingo Pueblo, also known as Kewa Pueblo, spent years as an isolated community—that is, until 2010, when a commuter rail station connecting Santa Fe and Albuquerque was built just two miles away. There’s no question that the station was an asset, providing the pueblo’s residents needed access to nearby urban centers. But even so there was a problem: There was no safe way for pedestrians to traverse the distance between the station and the pueblo itself.

The Santo Domingo Heritage Trail Arts Project emerged as a means to link the pueblo’s tribal members to the economic and educational opportunities that lie along the rail route. But the trail isn’t just important for its physical properties; it also represents a conceptual bridge between Native and non-Native thinking, marrying the strengths of both into a community-centric design that lifts up Indigenous values.

Photo: Courtesy of AOS Architects.

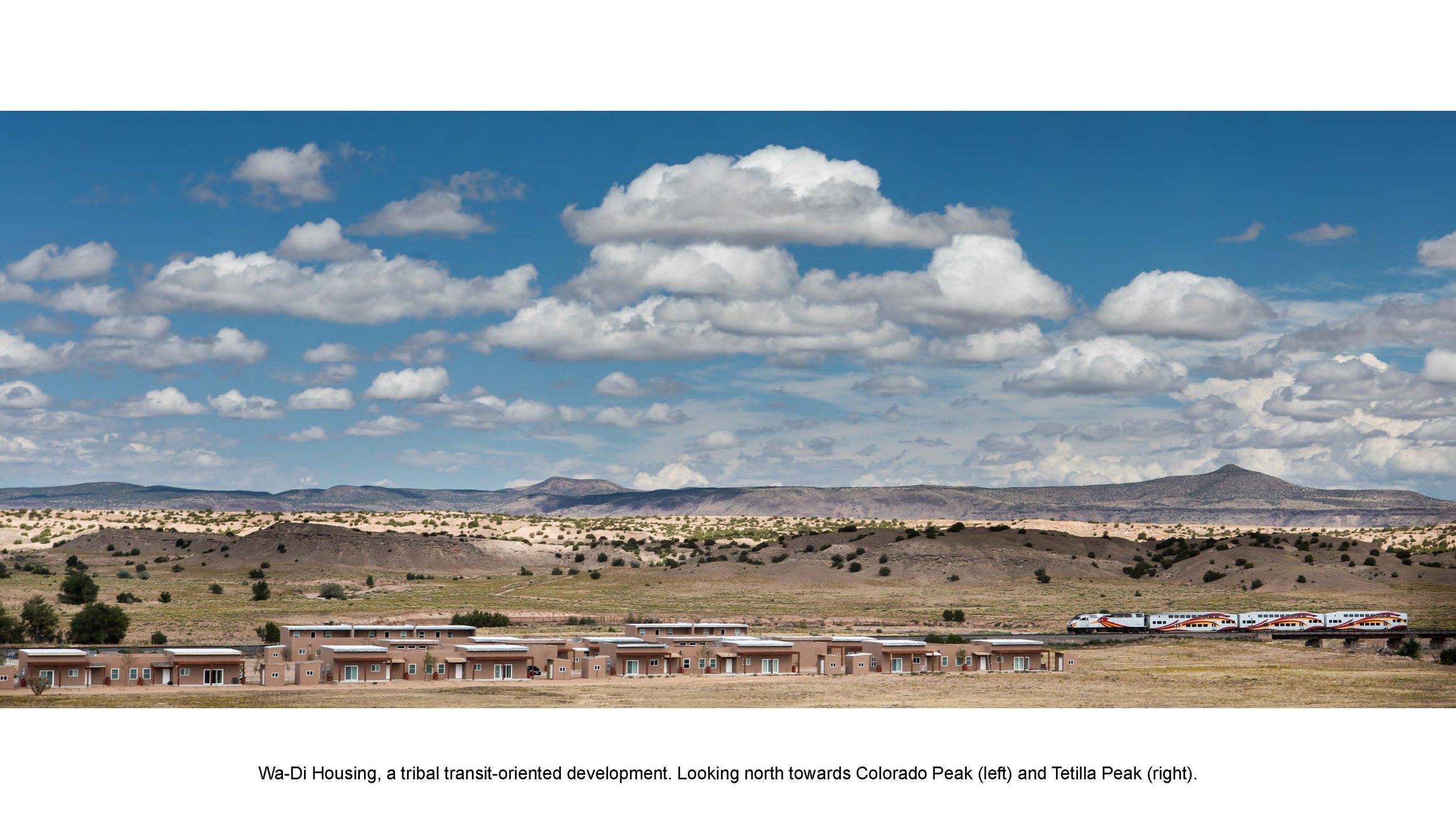

Architecture, as it’s commonly understood, has historically been dominated by Western thought, with Beaux-Arts and Bauhaus considered the exemplars of the discipline. But projects like the Heritage Trail and the nearby Wa-Di housing development—supported by non-Native architects and landscape designers but suffused with local, Indigenous input—is a manifestation of what’s possible when the two come together.

To this end, both the Wa-Di development and the Heritage Trail embody several of ArtPlace’s 13 themes, particularly in the physical and social realms. To be sure, the Heritage Trail transforms space and bridges differences, but at its core, the project doesn’t so much unite disparate worlds as it does solve a collective issue.

Solving a collective issue.

The projects at Santo Domingo were from their inception the product of collaboration. Wa-Di was designed by Atkin Olshin Schade Architects with the Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative (now the Sustainable Native Communities Design Lab at MASS Design Group) and members of the pueblo; what resulted was a 41-unit artist-centric development that hews to the Kewa culture, respecting the tribe’s preference for density and shared community spaces.

Similarly, the Heritage Trail is more than a pedestrian path connecting the pueblo to the train station; it’s also an experience designed to celebrate and lift up local culture. To this day, the area’s tribal members have maintained their traditional artistic roots, with almost 75 percent relying on selling jewelry, baskets, and pottery as their primary source of income.

One of the trail’s functions is to connect pueblo residents to opportunities in nearby cities, as well as bring tourists to the pueblo. But of equal importance was leveraging the community’s artistic capital to tell the story of the pueblo’s past, present and future. As such, those involved—including the Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative, Atkin Olshin Schade, landscape designers Olin Studio, and tribal leaders—developed a holistic plan for the trail, which features eight sculptural nodes designed by artists hired from the community.

Both Wa-Di and the Heritage Trail were made possible because all parties involved embraced the practice of listening. By and large, Western culture is ruled by an ideal that values bold assertions and loud claims. In Indigenous culture, the opposite is true. Listening to others, observing and watching are the primary vehicles for learning. The Santo Domingo projects developed as they did because our non-Native partners entered community meetings with open ears, as opposed to ideas to impose.

On a community level, we don’t yet know how the work connects systemically, as the projects at Santo Domingo are still too new for their full impact to be realized. What it has done is set a precedent for how we approach our work going forward.

From creative placemaking to creative placekeeping.

This ties into how we conceptualize creative placemaking. While this idea was conceived with the good intention of ensuring that the arts are incorporated into the community development process, “making” suggests that creativity can only be born of that which is new. In Indigenous communities, and what Santo Domingo seeks to capture, is instead the idea of creative placekeeping. Rather than creating from scratch, Wa-Di and the Heritage Trail bring to bear a cultural heritage that has long been in place, building on Native experiences and values.

Our job, then, is to elevate the notion of placekeeping beyond the niche universe in which such language is debated and cement its place in the mainstream. With Santo Domingo, listening to the community and empowering its members to take ownership of the process was indispensable to the projects’ development. Going forward, placekeeping should be an intrinsic component of development; as essential to a project as engineers or contractors. By continuing to demonstrate the ways in which Western and Indigenous thought can work in harmony, we can build toward a future that all can be proud of.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joseph Kunkel, a citizen of the Northern Cheyenne Nation, is the director of MASS's Sustainable Native Communities Design Lab based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. As a community designer and educator, his work explores how architecture, planning, and construction can be leveraged to positively impact the built and unbuilt environments within Indian Country.

This post is part of the series, Future of the Field: Cross-Sector Creative Placemaking Series.