How the Light Gets In

Narrative Power Building through the Arts

Nayantara Sen, guest editor

Years ago, in 2016, I was invited to deliver a workshop on artistic practices for disrupting structural racism for the Laundromat Project’s Create Change fellowship program for BIPOC artists. As I was digging around for content and inspiration to share with the fellows, I decided to return to my own creative roots: fiction and poetry. From my bookshelf, I grabbed Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, the cornerstone of race-explicit narrative and cultural analysis. Then, something surprising happened. I stumbled across a random dusty anthology and found a long-form essay by fiction writer E.L. Doctorow titled, False Documents.

In a limited print of this essay published in 2006, Doctorow made an electrifying case for why artists hold narrative and cultural power far beyond what our socio-political institutions can imagine or accommodate. He wrote,

“There is a regime of language that derives its strength from what we are supposed to be and a language of freedom whose power consists in what we threaten to become. The artist's opportunity to do their work today is increased by the power of the regime to which they find themselves in opposition. As clowns in the circus imitate the aerialists and tight-rope walkers, first for laughs and then so it can be seen that they do it better, we have it in us to compose false documents more valid, more real, more truthful than the true documents of politicians or journalists or psychologists. Artists know explicitly that the world in which we live is still to be formed and that reality is amenable to any construction placed upon it. It is a world made for liars and we are born liars. But we are to be trusted because ours is the only profession forced to admit that it lies — and that bestows upon us the mantle of honesty.”

A language of freedom? Whose power lies in what we threaten to become rather than what we are supposed to be? As a creative and writer who struggled to find belonging and purpose within the exclusionary, narrow confines of the “professional art world,” I was really drawn to this idea. I used it then to create a workshop called Your Art is Your Weapon on anti-racist and interdisciplinary craft techniques for the Laundromat Project. But then, Doctorow’s ideas burrowed their way into my psyche and began guiding me, gently and purposefully, towards arts-integrated narrative and cultural power building work.

Brochure from the LP’s Create Change 2016 workshop, Your Art is Your Weapon: Using Craft Techniques to Address Racism.

As I watched the growth of disinformation technologies, the lying and corruption of the political elite, the chaotic, farcical Trump presidency and the erosion of trust in both civil society and public, journalistic, and media institutions, I learned about the limits of fact-based persuasion and advocacy strategies to facilitate change. I learned that powerful narrative strategies — and the artists who use them — engage not just at the level of fact, but at the level of cultural meaning. (Nietzsche famously said “there are no facts in themselves. For a fact to exist, we must first introduce meaning.”) And I watched so many BIPOC artists shape cultural meaning through visionary, mobilizing work grounded in languages of freedom — even as they struggled to find sustainable resources and support. Doctorow’s ideas began to take on new relevance.

“Artists are narrative stewards who teach us languages of freedom and take us on visionary, truthful journeys towards dismantling regimes of oppression.”

These lessons helped me shape a set of animating inquiries that have guided my narrative and cultural work over the years. Artists are narrative stewards who teach us languages of freedom and take us on visionary, truthful journeys towards dismantling regimes of oppression. So then, how do we resource artists to culturally and materially construct our realities? How do we support them to create socio-cultural and economic conditions for our liberation? At the crux of these questions lies our ability to resource artists for narrative power.

Artist-serving organizations and arts philanthropy have a clear and integral role to play in supporting artists, especially BIPOC and artists from historically marginalized communities, in growing their narrative power. Given that we are experiencing volatile culture wars, narrative grantmaking across the board — in social justice, movement building, and arts and cultural philanthropy — remains alarmingly sparse. And even as artists strive to grow their narrative power, and demonstrate narrative leadership and innovative narrative praxis, there is still a perplexing gap: arts organizations and arts philanthropy neglects and disavows its shared role in narrative field building.

This essay, and its accompanying commissioned multimedia posts, are for arts funders interested in exploring the “why, what, and how” of arts-integrated narrative strategies. The featured stories and projects also offer instructive entry points to this question: “So what does operationalizing narrative strategies within arts organizations and building narrative power for BIPOC artists look like in practice?”

What’s Ahead

Kamayan, traditional Filipino communal feast where we dig in and eat with bare hands.

Think of this series as an introductory sampler plate at a delightful potluck dinner. You’ve been invited to dig in with curiosity and gusto! You’ve been asked to roll up your sleeves and get messy, because transforming narratives for liberation is playful, nourishing, wondrous, and experiential business. You are encouraged to eat with your hands, Kamayan style, as my Bengali and Filipino family does whenever we want to remember ourselves, our culture, and our home.

This essay is your first course, where you can engage with some high-level questions and principles on arts-integrated narrative strategy. As you progress through the next samplers in the series, you’ll encounter new projects, people, ideas, and approaches. (Or you might engage with pre-existing ideas differently, through the lens of operationalizing narrative strategies and praxis in your work.) The field-led examples range across types of work (projects, organizations, capsule initiatives, organizations, philanthropic collaboratives, reports, research, and recommendations), arts-integrated issue areas (food culture, Black wellness, gun violence, public memory, immigrant and migrant justice, restorative justice), and sectors and strategies (arts media ecosystem, pop culture for social change, creative placekeeping and place-based narratives, participatory narrative development, systems change, and embodiment). Taken together, these three focus areas demonstrate a broad range of narrative power building strategies with, by, and for BIPOC artists. And though I’ve attempted to curate across a range, the series is still of course a partial and incomplete snapshot.

Take the time to read slowly, savor, and digest purposefully, as you’ll find beautiful synergies and provocations threaded through the eight commissioned pieces. As you do, imagine what you might bring in the future to this communal feast.

Come, let’s dig in!

Resourcing Arts-Integrated Narrative & Cultural Strategies

Another Me by Flostitanarum, a visual artist and printmaker based in Indonesia. Created for Amplifer’s Well + Being mental health and wellbeing campaign.

“Narratives and culture can either restrict or expand the Overton Window, which directly affects our socio-political and material realities. Artists play with the raw materials of meaning-making, which is really the core skill for affecting narrative change.”

Narrative and cultural strategies are epistemic because they operate at the level of cultural meaning, worldviews, norms, and belief systems. This means they strategically work to affect why and how we believe and know what we do, and how we change. Narratives and culture can either restrict or expand the Overton Window, which directly affects our socio-political and material realities. Artists play with the raw materials of meaning-making, which is really the core skill for affecting narrative change. Audre Lorde wrote that, “the quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product with which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives.” Artists know how to shape this “quality of light” so that we can see, perceive, envision, understand, and ultimately transform culture with more ease. In this way, they influence the aperture, frame and range of the Overton Window. BIPOC and immigrant artists, and artists from historically marginalized communities, are especially equipped to shape narratives for liberation because they have survived conditions of narrative and cultural harm.

BIPOC artists are skilled, equipped, and positioned for narrative strategies — absolutely yes! But are they resourced in ways that build narrative power? No, not so much.

Arts organizations and artists — and the funders who resource them — are cultural arbiters that influence narratives by creating art, stories, exhibits, performances, experiences all the time. Art always carries information which is imbued with cultural perspectives and worldviews — in other words, art always transmits meaning and narrative. And just like there is no neutral narrative (stories always either advance or interrupt dominant narratives[1]), there is no narratively neutral arts or cultural organization. Yet the vast majority of American arts and cultural institutions and arts philanthropies do not claim their role, power and responsibility as narrative engines, influencers and producers— and as organizations that serve as valuable narrative field infrastructure.

This must change. Organizations and funders that resource and support artists and that have committed to deep racial and social justice work must now grow their praxis in engaging narrative strategies, because we are staring down the swift rise of authoritarian, xenophobic, white nationalist cultural movements that are capturing the cultural consciousness of the majority of Americans, and shaping our dystopian reality through effective narrative organizing. I don’t need to say much more to make a case for the need and urgency of narrative grantmaking for our survival. This clarity is facilitated by the growing terror we all feel as we read the news and witness the culture wars approaching a fever pitch.

Many field leaders and funders are responding to our urgent and growing need for narrative power by digging into learning, action and practice. Six years ago, as I worked to launch the Narrative, Arts, and Culture department at Race Forward, a national racial justice movement-building organization, and supported the curricular development of GIA’s racial equity training series for arts funders, the advocacy conversations centered around “why the arts sector really needs to prioritize race-explicit narrative strategies.” That’s now steadily being replaced with implementation conversations about “how we grow and practice narrative strategies for liberation.”

These days, I find myself in the wonderful company of fellow artists, cultural strategists, organizers, and funders who are bridging this gap in narrative implementation and praxis. Some are bridging the gap by funding artists for narrative strategies, others are innovating with research, tools, methodologies, and experiments that resource artists for increased narrative reach and impact. As a practicing educator in this space, who supports both field and philanthropic learning and strategies, I now encounter these specific questions all the time (sometimes multiple times in a week!)

“I get that we have to resource BIPOC artists to build narrative and cultural power, but how do I do that?

What does operationalizing narrative strategies within an arts and cultural grantmaking portfolio look like?

What are some ways that arts organizations and leaders are integrating narrative strategies?

As an arts funder, how can I learn across comparative examples from the field?”

I love the promise and possibility of what these questions spark for those asking and answering them. But even though there are the predictable frustrations of daily practice — as in, how will I actually support artists in implementing narrative change through my work? — it’s important to remember that the underlying purpose of narrative and cultural strategies is breathtakingly complex — as in, how can we collectively transform our culture to release who we are and what we believe, so we can claim our languages of freedom and become who we want to be? As my colleague Evan Bissell says, the work of narrative and cultural strategy is to “create material conditions that are more insistently human.” Doing this work requires uncertainty, inquiry, vulnerability, wonder, creativity, and being able to relish the generative space of not-knowing in order to learn, adapt, and change.

“Narrative change” work can variously feel sprawling, vague, jargony, opaque, or didactic — but it doesn’t have to be, especially for arts-integrated work. There are concrete examples of practitioners, funders, and artists who are integrating narrative strategies into their work — eight of them are showcased in this series. (There’s even a dedicated blog post about narrative tools made for and by artists!) And, there are learning communities for funders interested in narrative grantmaking, like Entertain Change: Philanthropy at the Pop Culture Collaborative.

Below, I share a set of six distilled principles on narrative practice that I have learned from working with the authors of this series, or from witnessing their projects unfold over the years. I offer these with humility as I continue to learn and, with the support of trusted co-conspirators, to grow my ability to operationalize these ideas in my work.

Principles to Guide Narrative Practice

Narrative strategies are inextricably entwined with cultural strategies; you can’t do one without the other. Narratives and culture shape and reinforce each other, and to affect durable narrative transformation, we have to act on and through culture. As explained in the Making Waves Guide to Cultural Strategy, “culture is both the object and agent of change”. Storytellers, artists, cultural workers, and culture bearers are therefore essential for narrative strategies and power building. This convergence between strategies for narrative and culture change is common within arts philanthropy as well, and the lineage of this overlap is explained in the Convergence Partnership’s Funding Narrative Change report. The authors of this report, Sen and Moore explain that many narrative grantmakers began their work initially as arts funders resourcing social justice storytelling and cultural production. “Artists were supported at least in part as storytellers, and storytelling was central to shifting narrative. Most of the experts in narrative are also experts in cultural strategies, and vice versa. The program officers involved in funding one are usually involved in funding the other.”

Narrative strategies involve composting dominant narratives and ideas about ourselves and our institutions.

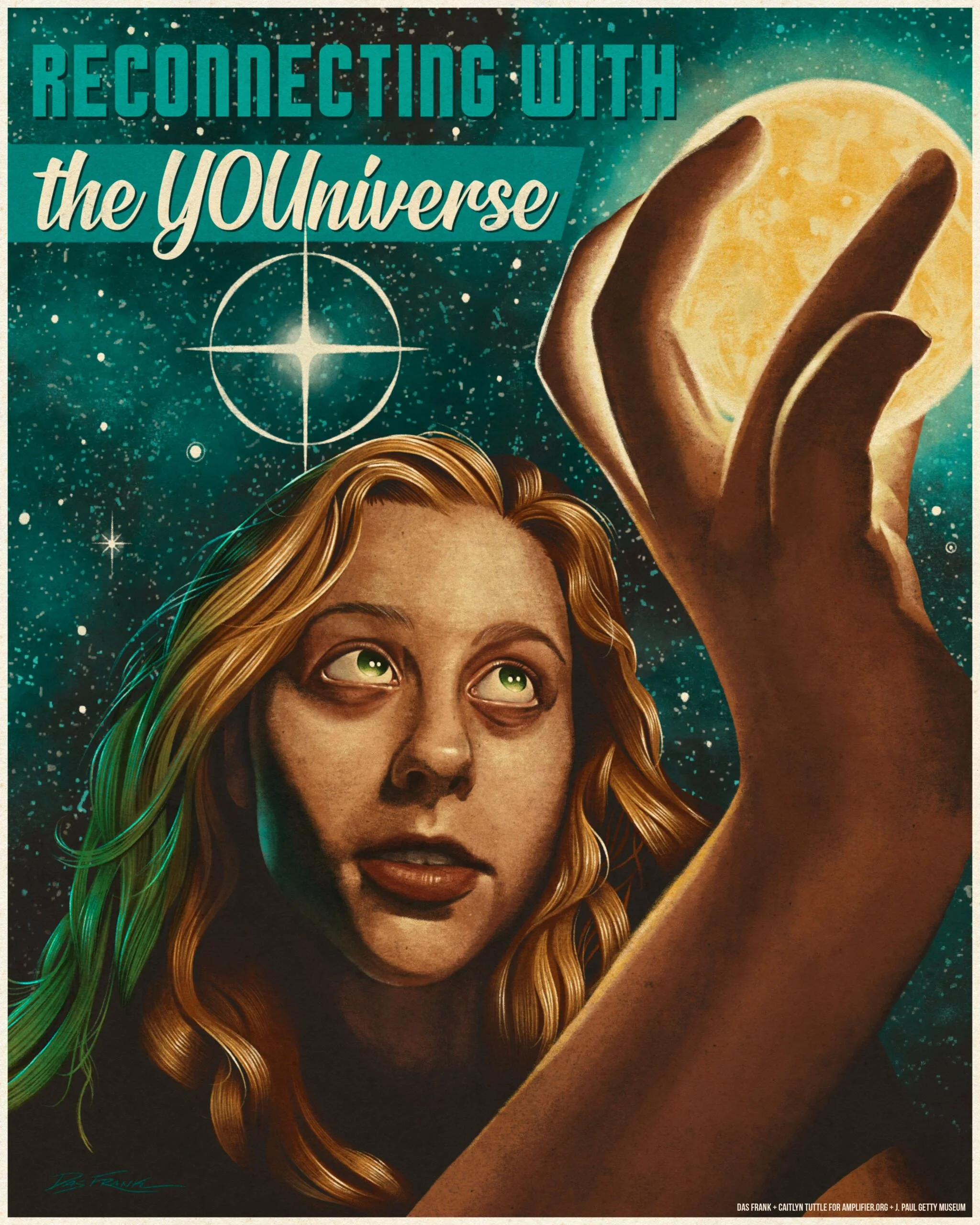

Reconnecting with the YOUniverse by Das Frank, based on a photograph by Caitlyn Tuttle. Created for Amplifer’s “Reconnecting With” Open Call for Teen Photographers

Harmful narratives are not just held “by those people out there” — they are also internalized and practiced by us within our own organizations. Narrative change work must be self-reflexive and grounded in the belief that not only is change possible and inevitable — but that we can change ourselves as we work towards a future of collective liberation. This involves interrogating how we, as arts and cultural practitioners and funders, manifest and uphold oppressive narratives through our bodies, stories, actions and institutions. It involves persistently returning to these questions:

What specific harmful narratives and ideas am I striving to change in our work?

How does my role interrupt, challenge or complicity maintain or advance narrative harm?

How does my organization practice politics of reparations, hold itself accountable to participatory narrative development with communities, and address power and resource imbalances for BIPOC artists?

Narrative Strategies are not just about changing peoples’ minds — they are deeply somatic, embodied, and experiential. Narratives live at the cellular level in our bodies and are created in response to broader social and cultural conditions, as well as learned and inherited intergenerational trauma and adaptation patterns. We experience and interpret narratives somatically through our bodies, not just in our brains. So relinquishing and excising long-held narratives is not solely an intellectual, cognitive or fact-based exercise. Narrative change must be experienced in the body, whether it’s individual bodies or collective organizational bodies.

Reconnecting with Ceremony by Mer Young, based on a photograph taken by Katie Medicine Bull. Created for Amplifer’s “Reconnecting With” Open Call for Teen Photographers.

This involves embodiment and movement practice, and pretty much any other artistic, creative or ceremonial practice that allows you to first sweat, release, exhale, catabolize, unclench

— before you can then rest, reconstitute, anabolize, rebuild, imagine, and re-animate new ideas, behaviors, and practices. Changing foundational worldviews in any person, group or collective requires imagination, spaciousness, abundance, trust, faith and safety — none of which work as ideas in abstraction. One has to feel these things emotionally, psychically, physically, and perhaps even spiritually. This is a process of becoming and all the mess that it involves, the unraveling, untethering, piecing together, and ultimately, the integration of new narratives and worldviews.

Explore this deeply in brontë velez’s essay, The Alchemy of Atonement, which asks readers to consider the roles that embodiment, ceremonial release, hauntings, memory and remembrance, atonement, cultural hospice care, and care for the earth play in guiding us towards a culturally and racially just future. The Alchemy of Atonement also includes two gorgeous, original short films, serotiny and between starshine and clay about Lead to Life’s public ceremonies to transform and alchemize guns from weapons of violence into life-affirming instruments and shovels.

Narrative grantmaking involves resourcing artists with narrative capacity and tools to support rigor, alignment, and experimentation. BIPOC artists across the country are yearning to grow their narrative impact and power, especially as we are being increasingly called on to respond to the waves of cultural and socio-political assaults. Funding artists to do crucial narrative meaning-making work is essential, of course. But as artist serving organizations stretch their capacity, infrastructure, and skills in order to support narrative goals and resource artists for visionary narrative change work, they are also struggling to find implementation-ready narrative tools, frameworks, research, and technical assistance. Narrative practitioners are now creating lots of powerful, accessible, and easy-to-use tools specifically for creators who want to integrate narrative strategies into their artistic work. Cultural organizations are launching narrative cohorts and design labs for artists, resourcing narrative networks for artists, and generating a diverse range of creative briefs, story platforms, narrative systems, and project ideation and design tools for artists to play and create with. Artists are experimenting with research and audience engagement strategies and tools to help strengthen the rigor, reach, and efficacy of their narrative work. Arts funders interested in growing narrative power should also invest in resourcing continued narrative tools, research, and pedagogy development for the field.

Narrative strategies should be participatory, communal, and accountable. This sounds so obvious, I know. And we are of course well-trained, well-intentioned, veteran artists, field leaders, and funders with clarity, conviction, and ethics around equitable practice and participatory program design. But narrative and culture change work brings some unique and complex challenges — the business of sustainably transforming narrative conditions and worldviews through arts and culture is slippery, messy, inconsistent, difficult to measure in one or two year grant cycles, and hard to assess at any scale — whether individual or societal, national or regional. It’s generally rife with contradictions. Funders rightfully ask me questions like, “We already have trouble speaking to the concrete long-term social justice impact of art, so how do we now show the narrative impact of said art? Did my grant portfolio generate useful narrative learnings? Did the artists and culture bearers advance narrative changes in their communities? How will we know if the artist cohort measurably achieved narrative impact?”

Together We Can Thrive by Monica Canilao.

Answering these gnarly questions can become tactically easier when a smaller set of people (mostly people with privilege and positional power) are tasked with answering them. But if narrative and cultural organizing projects are designed without thoughtful attention to deep participatory design — including clear understandings of how place-based narratives and communities are being activated — and if a few people with privilege and power control the story or the process, then we undercut our ability to move narrative strategies that resonate and have “stickiness.” Just as all humans reject stories in which they cannot see a future for themselves, excluded communities reject narrative and cultural strategies where they do not see their future represented. Social practice artists who work deeply in and with communities know this in their bones, and they are familiar with the fissures, contradictions, and inconsistencies that emerge from participatory narrative development processes. These narrative fissures and inconsistencies make for challenges in assessing impact, sure — but these cracks are also liminal spaces where the lights get in. Tending to these warps and inconsistencies, the paradoxes and dissonances in stories, that’s what shapes the “quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives.” This collective and iterative narrative process is essential for cultural organizing work to be truly participatory, accountable, and ultimately effective. As the Constellations Initiative team explain,

“In culture change efforts, who holds narrative power cannot be overlooked. It is essential that culture makers in community, as well as directly impacted communities have participatory methods in shaping the narratives that are employed as culture change. Cultural strategy allows mechanisms for narrative change to be rooted in communities in authentic and inspiring ways. Rather than narrative priorities being generated from top-down and centralized mechanisms, cultural strategizing and organizing can ensure that narrative choices reflect the creativity, vision, agency and decision-making power of those most impacted by systemic oppression.”

Narrative strategy involves activating narrative networks for BIPOC artists and creators for systems change. It’s important to resource and fund artists to learn, experiment and produce collaboratively in narrative networks, towards shared narrative and systems change goals. It’s difficult for individual artists to do narrative work for several reasons (narrative tools and research are sparse or expensive, measuring progress and impact for individual projects on massive narrative goals is discouraging, and so many other reasons!). Funders like the Pop Culture Collaborative are organizing powerful narrative networks for cross-disciplinary BIPOC artists to experiment, learn, and grow their power. Within narrative networks, artists can build shared work, align with narrative goals and priorities, innovate with audiences, and stretch their creative muscles towards narrative goals. Artists in narrative networks can also collaborate with organizers and systems changemakers to support efforts for reimagining and transforming systems.

In Bridgit Antoinette Evans’ Open Letter to Arts Funders, she examines how “artists and other content creators work together to develop and produce artistic projects that are wildly unique in their form and content while also sharing some narrative priorities.” In the letter, Bridgit writes,

“Becoming America grantees are able to access the creative advice and collaboration of dozens of other network members as they develop, produce, and distribute their work. And as their work makes its way into the world, their stories create a surround sound experience for audiences—a ‘call and response’ as shared narratives create a chorus across the films, televisions shows, digital videos and series, podcasts, songs and music videos, books, essays, murals, and other content that millions of people engage with.”

Reimagine - Patrisse Cullors by Noa Denmon.

We are headed into times of increasing tumult and grief, as attacks on women, trans and queer communities, people of color, disabled people, immigrants, migrants and refugees, and our planet escalate. Yet even though the injustices we face are perilous and distressing, I do know that we were made for these times. And when I think of what’s really required of us to build a resilient arts sector and a just, thriving, free, and healthy country, I am clear and convinced: BIPOC artists, and the organizations that serve them, must be powerfully resourced to build narrative power now so that we might propel our communities from a culture of death and necrosis towards a culture of wellness and freedom.

There is life-affirming learning and work ahead, and so many good people on the road with us. Please use this small potluck offering on the GIA Reader as another reason to find each other — as fellow dreamers and weavers, friends and co-conspirators, cooks and comrades. Read, feast, relish, digest. And in the spirit of potlatch, — the Indigenous Chinook language word of Kwakiutl - Nootka people that means “gift-giving,” that reminds us that real wealth is measured by generosity and by what we share, not by what we accumulate — please share what you learned with colleagues and interested peers.

NOTES

[1] See pages 5-6 of Butterfly Lab’s narrative toolkit on terms and definitions on stories, messages, and narratives.

COVER ART

TITLE courtesy of ORG, one of the featured contributors to this series. Photo by .

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nayantara Sen is a Bengali immigrant, a trilingual storyteller and fiction writer, a narrative and cultural strategist, and a social justice educator. She is the Director of Field and Funder Learning at the Pop Culture Collaborative, the Lead Designer and Narrative Strategist for the Butterfly Lab for Immigrant Narrative Strategy, and the previous Director of Narrative and Cultural Strategies at Race Forward.

For the last 15 years, Nayantara has worked at the intersections of arts and culture, narrative and story-based strategy, racial and gender justice, immigration, movement strategies and equity-building for arts institutions. Nayantara is a recovering arts administrator who has previously held staff, curatorial and consulting roles in museums, film festivals, theatre and community-based arts organizations. Her artistic background is in oral history, creative fiction writing and Theatre of Oppressed.

She was the Lead Designer of the NYC Racial Equity in the Arts Innovation Lab, which equipped 60 NYC arts-producing organizations and museums with strategies for racial and cultural justice. She is the author of Creating Cultures and Practices for Racial Equity: A Toolbox for Arts and Cultural Organizations, the widely taught Cultural Strategy Primer, and the Storyline Partners’ Stories for Change toolkit. At the Pop Culture Collaborative, Nayantara works closely with arts and social justice philanthropy to advance learning and action on narrative strategies. She also partners with a wide range of arts organizations such as the Constellations Fund at the Center for Cultural Power, Naturally Occurring Cultural Districts-NY, and the San Jose Museum of Art.