Disrupting the Map: Strategies for Funding Cultural Sovereignty in the Global South

David Mura

Moderator/Organizers: Clarissa Crawford, Ericka Jones-Craven, Jaime Sharp

Speakers: Ananya Chatterjea, Ashe Helm-Hernandez, Shey Rivera Rios, Joe Tolbert Jr.

From the U.S. South to Puerto Rico and across diaspora communities, artists are cultivating cultural power, resisting erasure, and building networks of solidarity in the face of state-sanctioned neglect, political repression and economic divestment. Yet traditional arts funding often fails to meet these artists where they are, or recognize the strategic brilliance of their resistance. This session will center artists and cultural organizers from the Global South who are creating sustaining movements at the intersection of arts, activism and community care.

We will explore how funders can shift from transactional to transformative relationships, resource cultural work as movement infrastructure; and strategically support coalitional-based initiatives across BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and immigrant communities. Participants will leave with concrete tools to apply place-based, justice-centered grantmaking practice.

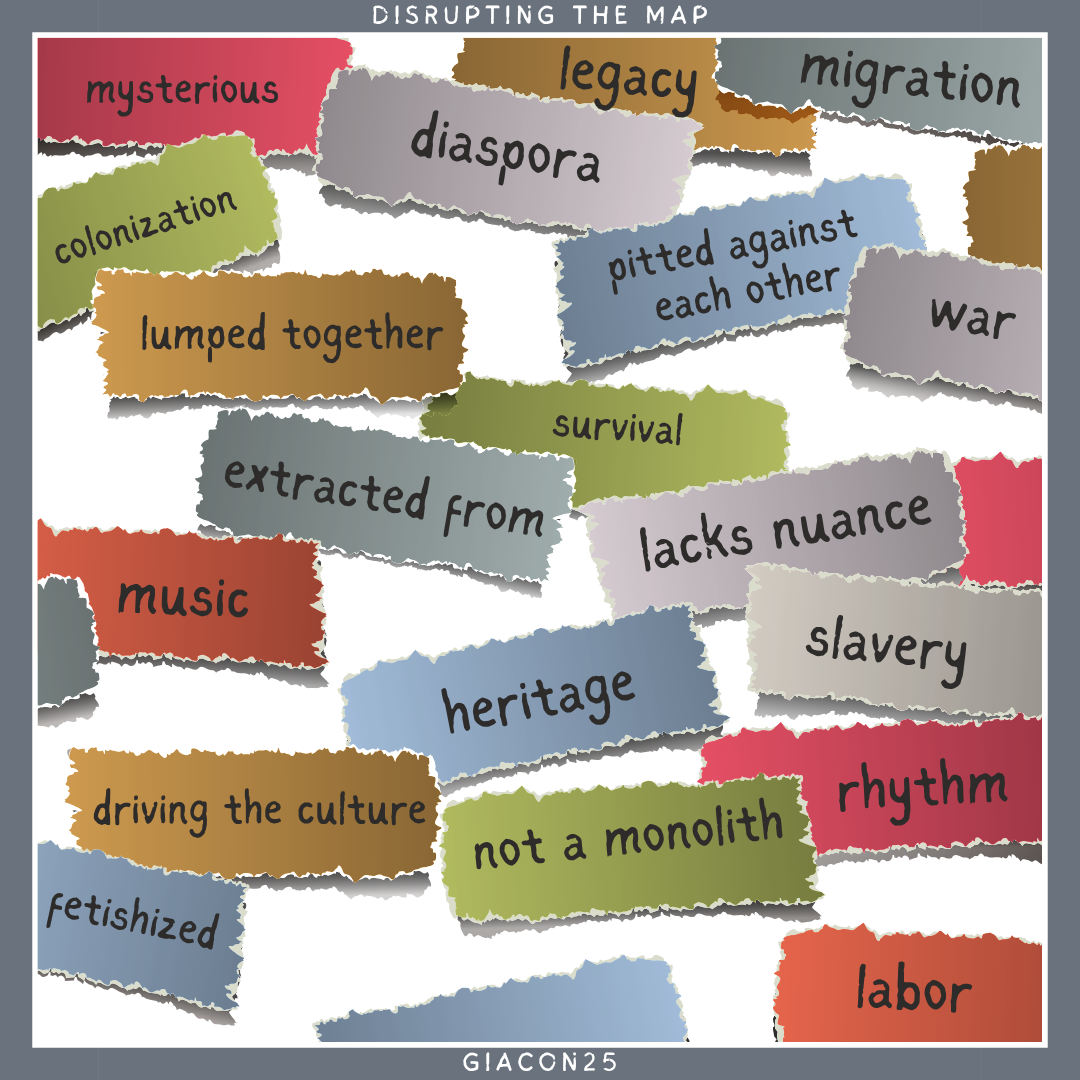

Ericka Jones-Craven, organizer, and Clarissa Crawford, moderator, asked the audience: How do you define the Global South?

How are multiple Souths enmeshed/implicated in each other?

Responses from the session. attendees via Mentimeter.com

Ananya Chatterjea — Anaya Dance Theater (ADT)

Ananya shared, “I live and work on the land of the Ojibwe and Lakota communities, and I serve as the artistic director of Ananya Dance Theater, where Black and brown women create dance and practice at our Shawngrām—our center for resistance.”

She described her roots in the Global South as a Bengali woman, emphasizing a shift away from nation-based identity toward language, culture, and relationship. At ADT, their work focuses on building deep connections across multiple communities of color.

“The South is active in all that I do,” she said—disrupting imposed maps, claiming cultural specificity, practicing justice-centered activism, imagining beyond colonial nation-states, and continually asking how to bring the desire for liberation closer to lived reality.

Ashe Helm-Hernandez — Director for Philanthropic Organizing, Funders for LGBTQ Issues

Ashe Helm-Hernandez has lived in Atlanta and worked on organizing there, but Ashe now works in Louisville, where there is more resistance to the work Ashe is doing. The Trans Future Funding Campaign, TFFC Steering Committee, raised 10 million dollars, and they try to make sure they know who they are working with in their grants. Part of this entails giving without saying it should be done in certain ways with certain outcomes; instead, let the people and organizations they give funds to determine what the people need.

Philanthropic Organizing distributes funds to many groups and serves as an intermediary for these organization in the south: Funds for Trans Generations, Out in the South, Campaign for Southern Equality, Queer Mobilization Fund, Third Wave Fund, Astraea, Transgender Strategy Center, and the Trans Justice Funding Project.

Ashe underscored that power is shaped by perception—and shifting perception requires creativity, strategy, and space to imagine new approaches. They shared an example from Southerners on New Ground (SONG): when they couldn’t secure a meeting with a judge about supporting people navigating the justice system, they delivered a symbolic “ticket”—a visual metaphor for the urgency of their request. The judge responded immediately.

Ashe offered additional examples of creative resistance and community care: partnering artists with literacy programs; making puppets for guerrilla theater; queer brown folks gathering for mutual protection; and producing billboards to defend Trans youth. “The South is where we’re disrupting the map,” they noted, “and confronting the reality of being deemed illegal.”

From L to R: Clarissa Crawford, Ananya Chatterjea, and Ashe Helm-Hernandez

Shey Rivera Rios — Studio Loba

Shey Rivera Ríos, who has organized in the arts across Puerto Rico and Rhode Island, spoke about the role of artists in shaping policy and building cultural infrastructure. They emphasized the importance of what often goes unseen—the slow, collective work of creating and moving in partnership with others. The point is not only the outcome; it’s how people are transformed and empowered through the practice itself.

Shey asked, “How do we protect what we build?” They reflected on migration, extraction, and the reality that many of us are multi-geography people—living in one place while supporting family in another, navigating diasporic identities, and holding ties to both the North and the South. They noted that Trans and queer communities remain radically underfunded and asked, “Where are the queer and Trans figures in our own histories?”

Artistic practice, they argued, must confront these gaps and questions. Shey shared several examples: a project where participants reclaimed the steps of an old community museum; another in Puerto Rico where artists created their own symbolic currency decorated with figures from Puerto Rican history, asserting cultural independence; and work in Colombia with cultural elders and practitioners who formed collaboratives and exchanged photographs as a way of passing on wisdom, memory, and intergenerational connection.

Through these practices, community bonds deepen, histories are honored, and people strengthen their capacity to build—and protect—shared futures.

Joe Tolbert Jr. — The Waymakers Collective

Appalachia is often referred to as the forgotten South, said Joe Tolbert. The work of Waymakers involves re-narrativizing ourselves: Art and artists are crucial to that work, whether it’s working on Black Lives Matter in the mountains, organizing protests against the building of prisons, or supporting artists to tell their new story. The work is community-controlled, rather than the ways land and labor were exploited and extracted historically. Ironically, this is often the wealth that created foundations.

Self-determination, Joe emphasized, begins with individuals and expands outward into community. If people aren’t equipped to govern themselves and work collectively, the futures they imagine can't materialize. Cultural organizing isn’t just about artistic output—it’s about the practices and processes that shape culture itself. Waymakers’ approach is rooted in solidarity with artists and organizations, standing with them rather than exercising authority over them. Artists, Joe noted, are essential for imagining new possibilities. In one project, Waymakers supported undocumented artists who envisioned a “green book” for undocumented queer and trans immigrants.

Joe spoke with urgency about safety for queer and trans communities. He defined safety as the ability to create, organize, and share resources without fear of harm or exposure. He shared that, over the past year, Waymakers received fewer grant applications. When he reached out to understand why, one organization in a small Southern town said they feared that publicizing their work could lead to retaliation or violence. As a result, Waymakers awarded the grant but did not publicly describe the funded project. This theme of safety—and the risks tied to visibility—surfaced repeatedly across other panels.

How are you all balancing being seen and being protected? What would it take for funders to become co-works in that situation?

Shey discussed how they were going to do an exhibit at a university, but the university pulled out a piece that they did criticizing the church. So, their gig was cancelled. But, students, faculty, and community protested, and from this, we understand that safety, in part, means you are not alone; you are part of a community. Our art practices can build these community connections, and these connections are a source of power and protection.

They also noted the global dimension of this issue: Colombia has one of the highest rates of violence and repression against artists. How, then, do we protect artists and activists in other countries? Shey offered an example of an artist kidnapped in Mexico who—unusually but fortunately—had ties to Spanish diplomats. Those diplomats intervened, threatening diplomatic consequences and securing her release.

“This case of enlisting the help of Spanish diplomates to protect an artist in Mexico illustrates an old principle of power—If you are in conflict with someone at your level of the organization or power, you need to cultivate allies who have greater power. Robert Greene’s 48 Laws of Power should be required reading for all those involved in the arts, grantsmakers, organizations, artists and members of the community. ”

Ananya – I wish that funders would do their homework and research. Artists are dealing with different kinds of oppression, in India, here. Don’t go with easy facile notions of difficulty; if we do justice work it’s a complex multilayered process so do the work of research if you’re a grantmaker.

Ashe – The One percent all know each other. Largest funder of LGBT funding is at World Economic Forum said we’re going to stop funding domestically. We need to push against set limits for funding, we need to fund new leaders.

When grantmakers say we’re protecting our reserves, well, this is the time you need to deplete your reserves. There are powers who want to destroy/eliminate us. If you don’t use your funds now, there may not be a future for our communities. How do we navigate these emergencies and attacks so that folks are not just relying on one government or funding backing?

How can censorship be used to an advantage, especially in sensitive communities?

From L to R: Ericka Jones-Craven, Shey Rivera Rios, Ashe Helm-Hernandez, Ananya Chatterjea, Joe Tolbert Jr., Clarissa Crawford, Jaime Sharp

Censorship affirms truths that the system wants to keep hidden, get information about what system fears and how it is attacking back. Censorship can create energy to organize and empower the community. Speaking out against censorship encourages others and gives them courage. Fighting against censorship is fighting to change the narratives supporting the censorship, the narratives used as rationale for the censorship. We need to continue to tell the stories of how people have been silenced and erased; we need to support artists who remember the resistances.

Can you give an example of bias in funding that shapes decisions and a solution that can happen instantly?

What is legible to funders? That’s a bias we need to address. We need to fund experimentation, fund things that aren’t like the things your organization has funded, challenge yourselves to be open to experimentation and newness, and funding forward. Work on having more dialogue with artists, organizations, and communities instead of just producing one thing. Do more sight visits, talk to more people. Recognize that social practice is now a practice of art. We need funding for infrastructure, such as COVID tests for artists. We need to think of ethnicity not as an essentialist identity or something that is set, but a process that is continually unfolding and changing.