Redefining Philanthropy Standards as Choices

by Adriana Abizadeh-Barbour

The Power of Imagination in Shaping Futures

Practicing futurists, like myself, are constantly reimagining the myriad of potential futures that exist and stem from singular decisions and moments in time. The possible choices that someone could make, expected reactions (for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, Newton’s Third Law of Motion), and ultimately determined outcomes. You may ask, “What is the desired future and for whom?” I would respond: A future where everyone has their basic needs met and opportunities afforded to them to access self-actualization and self-determination.

Imagination is not a luxury—it’s a discipline. A survival tool. A radical act in a world that tries to convince us that things must remain as they are. Imagination allows us to move beyond reform and into transformation. To dream of a world without police violence, without prisons, without poverty—not as utopian fiction, but as a real, lived possibility. It’s the groundwork for liberation. It’s what compels us to keep moving forward, even when the winds seem to be blowing the other way.

Community Models That Show Us What’s Possible

Everything around us is signaling a period of regression and entrenchment. With everything going on in the federal landscape, from the administration to policy and markets, there are local, community-led examples of what is possible when we imagine and dream that show us how to move with intention towards a desired future. In Philadelphia, Kensington Corridor Trust (KCT) – the organization that I lead – is decommodifying real estate for collective ownership. We are acquiring land and real estate from the speculative market and placing them into a trust for the neighborhood to directly own, govern, and control perpetually. Through the collective ownership of these assets, we are working to build neighborhood wealth, while preserving affordability and developing a replicable framework for neighborhoods to self-determine their futures.

None of this work is possible without philanthropic support. And given the moment we are in, philanthropy has a choice to make. As a sector with an abundance of power, privilege, and financial resources, philanthropy could choose to mirror federal sentiment and retreat, failing to meet the moment. But what our communities need and what our movements are asking for is clear: it’s time for philanthropy to use its imagination, consider a different, more equitable future, and redistribute its wealth to help make this future a reality.

Redistribution: Moving Money Without Strings

Redistributing wealth is hard work. It requires a reckoning with privilege, with history, and with the stories we’ve told ourselves about merit, value, and ownership. I’m talking about the deep, often uncomfortable work of interrogating where that wealth came from in the first place—and what it means to return it in a way that builds power, not just provides charity.

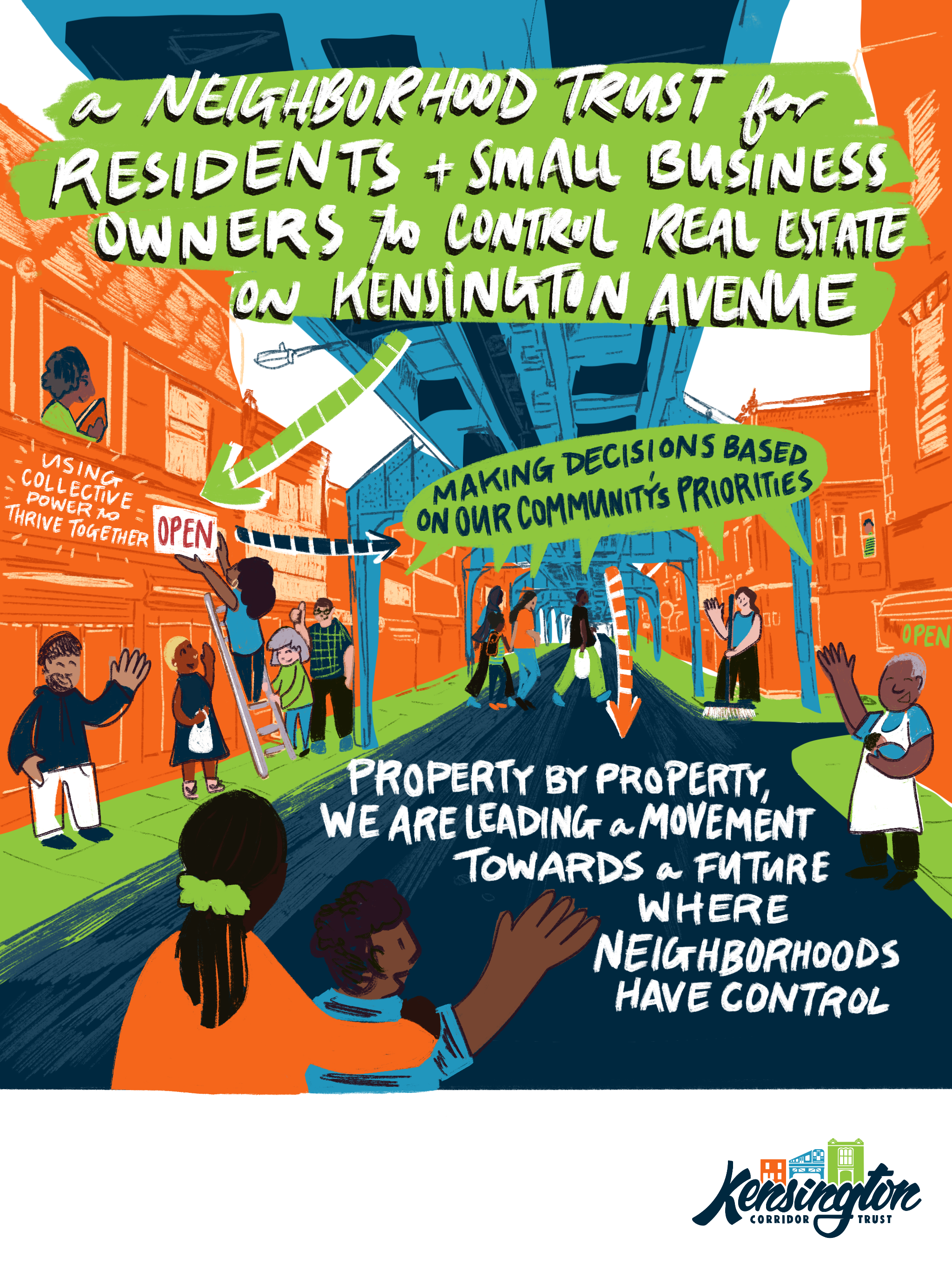

Building community power on Kensington Avenue — where residents and small business owners come together to reclaim real estate, make decisions rooted in shared priorities, and shape a future where neighborhoods have control.

Text across the image reads: “A neighborhood trust for residents + small business owners to control real estate on Kensington Avenue.” Additional phrases include “Using collective power to thrive together,” “Making decisions based on our community’s priorities,” and “Property by property, we are leading a movement towards a future where neighborhoods have control.”

Kensington Corridor Trust is building community wealth one property at a time — with 31 assets in trust, 42 units under development, and 10 thriving local businesses already operating in KCT spaces. Photo credit: Avery C. A. Sponholtz.

On the left, a photo shows a man standing outside a gray brick building with an orange awning numbered 3312. On the right, a colorful infographic displays key stats: “31 assets in trust,” “42 units under development,” “26 permanently affordable units currently leased,” and “10 businesses in KCT spaces.” A “Support Local Business” badge highlights local enterprises including Fatou’s Hair Braiding, KC Tax Services, Philly Mural Arts, and others.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE COVER ART

We need to reassess risk from the perspective of those seeking funding, not from the position of the financial risk to a wealth holder’s portfolio or a foundation’s endowment.

From my vantage point, wealth redistribution means moving money without strings, in ways that communities are trusted to decide what they need. Wealth redistribution, at its most powerful, is about shifting who gets to make decisions—not just who gets resources. Redistribution is not solely about wealth, but also power—it is an act of reparation. At KCT, our power table (governing body) is comprised of residents and small business owners from our service area zip code. Outsiders are not allowed to govern the collectively held assets. Those neighbors, most of whom are low- and moderate-income folks, decide what capital we accept, how it is deployed, and ultimately how it will provide collective benefit back into their neighborhood. They hold the power. They make decisions rooted in their lived experiences and use their imagination to build a vision for their neighborhood that is both possible and sustainable.

I understand that for some funders and wealth holders, wealth redistribution feels daunting. It can bring up fear—of losing control, of doing it “wrong,” of being critiqued. And I want to say: that’s okay. Feeling challenged or uncomfortable is not a reason to stop; it’s a reason to go deeper. I invite funders to partner with us in this critical work of imagining a new paradigm. To recognize that reparations aren’t a radical idea; they’re a moral imperative. That ceding power can lay the groundwork for beautiful new beginnings.

I’ve met some of the funders who have begun to walk this path—those who take the time to build genuine relationships with our team, who offer capital that’s patient and values-aligned, who look inward and revise their internal processes to reflect justice and dignity. At KCT, we’ve done the work to educate, advise, and organize funders, and it all began with genuine relationships. This resulted in the funders who increased their annual grant when they saw our staff capacity being tested, who sent an extra unexpected grant because the world is on fire, and the funder who sent me a beautiful flower arrangement when I returned to the office after some time off for my nuptials. They recognize my humanity and the humanity in our work.

So, when I say redistributing wealth is hard work, I’m naming the emotional labor, the logistical complexity, and the cultural shift it demands. But I’m also naming its necessity—and its promise. This isn’t just about shifting money. It’s about shifting mindsets, behaviors, and entire systems. It’s about funders and institutional philanthropy trusting people to build the future they deserve.

“We need to reassess risk from the perspective of those seeking funding, not from the position of the financial risk to a wealth holder’s portfolio or a foundation’s endowment. ”

Building The New: Collective Ownership Projects

Collective ownership projects often operate under enormous constraints—scraping together resources, patching together capacity, and doing far more with far less than is reasonable. And yet, we persist. At KCT, we are creating permanently affordable housing and commercial spaces without government funding. This means constantly hunting for integrated capital grants and low-interest debt to support the acquisition, redevelopment, and reactivation of real estate for collective ownership and neighborhood wealth building. Integrated capital affords us the ability to keep up with fast-paced real estate markets, prioritize local subcontractors in our redevelopment, and center art, culture, and history in place-based design. We do this in a neighborhood where the average household income is just above $26k per year. To experience that level of poverty is not for the weak or the unsure. Every day, you make difficult choices of survival and often must rely on community infrastructure and the social safety net to have your basic needs met. Like KCT, many of the other projects in the ecosystem of collective ownership are primarily led by folks of color, immigrants, and leaders with lived experience—individuals who understand the stakes because they are the stakes.

Like me, they know what it means to live in housing that is unsafe or unaffordable (and/or to be unhoused), to try and access healthcare without insurance, or to navigate education systems that weren’t designed for their thriving. These lived experiences shape the vision they hold for their communities—visions that are rooted in care, accountability, sustainability, and justice. Philanthropy must decide: will it meet these leaders where they are and walk alongside them, or will it continue to operate as an arbiter of worthiness from a distance?

All too often, we revert to industry standards and societal norms. The fact is that nothing should feel “normal” about unaffordable housing, commoditized higher education, or mass deportation. These are not the only areas where we need deeper transformation, but they are policy arenas I have worked in directly. They provide a lens for critique and reflection on the choices that continue to be upheld as acceptable standards in the American experience.

A dear friend of mine, Brandon McKoy, now the President of the Fund for New Jersey, has always said that “budgets are moral documents.” If, in fact, as a society, we practiced collectivism, our budgets would look vastly different. We would increase funding for mental health, equitable educational access, housing, and food security, just to name a few. We would ensure that our neighbors had their basic needs met; that our seniors could age in place with dignity and without having to choose between paying for housing or eating.

We must ask ourselves: how did these norms come to be? Who benefits from them, and who is harmed? Unaffordable housing is not an accident—it is a consequence of decades of disinvestment, redlining, exclusionary zoning, and speculative real estate practices. The student debt crisis didn’t appear overnight—it emerged through policies that systematically defunded public education while privatizing profit. The immigration system was not broken by mistake—it was designed to be punitive, racialized, and dehumanizing.

Standards are choices that have been made and are upheld by people in power. For the people in the back, I will say it again. Standards are choices. Choices that have been made and are upheld. Upheld by people. People in power.

Reimagining Philanthropy’s Role and Responsibility

Instead, knowing this truth, it could become standard for philanthropy to direct integrated capital towards projects meeting the community’s self-determined needs. Knowing this, philanthropy could identify new ways to redistribute wealth without placing the burden of education and information sharing on the organization seeking funding. It could also benefit from additional tools in the funding toolbox, such as planning grants, multi-year general operating dollars, and capacity-building support.

Let’s go further—what if it became standard to provide reparative funding? To not just “invest” in the future, but to acknowledge and redress the past? What if philanthropy recognized that many of the largest foundations in this country were built on the extraction of labor, land, and wealth from BIPOC and immigrant communities, and therefore have a moral and material obligation to return those resources? What if instead of relying on grantees to fill out endless logic models and spreadsheets, funders took on the labor of learning—reading the history, talking to community members, and letting go of the myth of objectivity?

What does it look like for a funder to be in right relationship with a grantee? For me, it means directly asking me what I need, not assuming. It means moving with intention to reduce the power dynamic that exists between us. It means continuing to show up when things get messy and hard. The strongest relationships I hold within the philanthropic sector are the ones with our grantors and investors who have prioritized our relationship over the money.

Money is a necessary tool for change in our societal construct, but capital alone can’t undo harm, it can’t undo disenfranchisement, and it can’t undo the choices of our past.

And yet, that doesn’t absolve philanthropy from the responsibility of trying. In fact, it’s an invitation to imagine and then deliver a shift from transactional giving to transformational relationship-building. Philanthropy must learn to sit in discomfort, to be honest about its complicity in extraction, and to surrender the illusion of control. Listen to and trust movement leaders; shift the power paradigm away from wealth holders and towards solutions led by impacted folks. To be in right relationship is to be present, not only in the gala moments of celebration but in the conflict, the ambiguity, and the grief. It is to accept that community-led solutions may not align with your strategic priorities, and to fund them anyway.

“Philanthropy must decide: will it meet these leaders where they are and walk alongside them, or will it continue to operate as an arbiter of worthiness from a distance?”

Learn to Unlearn

Philanthropy isn't a sector that gets to work in a vacuum. Be informed by best practices (like you expect of grantees - wink, wink). I encourage leaders in philanthropy to invest in themselves. That investment can take many forms—cultural competency training, political education, coaching on trauma-informed practices, or simply spending time in the communities you fund without an agenda. Invest in your learning journey so you can support folks on the ground in their journeys to build new futures. Go to the block party. Attend the tenant meeting. Volunteer without making it about a metric you include in your impact report. This is the most impactful way to meet your partners where they’re at. Learn how to listen deeply, not just to reply but to understand. Leadership in philanthropy means unlearning the assumption that expertise always resides in the office towers and not in the church basements, the barber shops, the corner stores, and the front porches of our neighborhoods.

Every day, I use my imagination to co-design alongside other practitioners towards the desired future. I choose to operate from a space of abundance, not scarcity. I choose my community and those I want to partner with. You see, we can set new standards and work towards a new economy that centers people and relationships.

“Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.” - Arundhati Roy

That future breathes through the work of mutual aid groups that deliver groceries to immigrants and elders without asking for documentation. It breathes through the efforts of collective ownership models reclaiming parcels for permanently affordable housing. It breathes through youth councils, designing policy recommendations for their cities. And it can breathe through philanthropy, too—if only it’s willing to listen and truly trust and follow the communities they invest in.

So let us not be discouraged by the signals of retrenchment we’re seeing today. Instead, let them sharpen our resolve. Let them remind us that our work was never meant to be easy. Let them push us to imagine more boldly, organize more strategically, and love more fiercely.

The future is not something that happens to us—it is something we build. And we build it best when we are in right relationship with each other, when we reject scarcity and embrace shared power. When we remember that transformation is not only necessary—it’s already underway.

Adriana Abizadeh-Barbour is the executive director of the Kensington Corridor Trust, a nationally recognized leader who brings expertise in public policy and collective ownership models. With a focus on racial and health equity, Adriana has led transformative initiatives addressing the intersections of housing, immigration, and poverty.

Better Sharing by Pietro Soldi for Creative Commons; updated by Grantmakers in the Arts (2025).

Follow Pietro Soldi on Instagram at @pietro.soldi. The Greats is made with hope and love by Fine Acts.